Judge Connolly Questions Counsel’s Grasp of Informed Consent, Agency Law, and Even Basic English

Delaware Chief Judge Colm F. Connolly ended 2023 in dramatic faction, detailing his findings that patent monetization firm IP Edge LLC, a related consulting firm, and the individuals behind them had together engaged in a sweeping “fraud” through their unusually structured patent assertion model. That order teed up various “consequences” for those involved, among them a set of disciplinary referrals for the attorneys representing the IP Edge-linked plaintiffs under scrutiny based on a variety of professional rule violations. Now, Judge Connolly has grilled the attorneys for two more of the plaintiffs in IP Edge’s web about whether they engaged in some of the same ethical violations—including one of the same litigators tagged in the court’s prior decision, Jimmy Chong (of Chong Firm PA), as well as his cocounsel David Bennett (of Direction IP Law). In a January 17 hearing, an increasingly irritated and incredulous Judge Connolly questioned their grasp of the legal and ethical issues at play, concluding that Chong had earned a second disciplinary referral, and ordering a conspicuously forgetful Bennett to produce documents in order to lay out some basic facts.

Under the primary IP Edge monetization model under scrutiny by Judge Connolly, individuals with little to no prior experience with patent monetization would be selected to become “passive investors” in LLCs to which patent assets would be assigned and which would then file suit against defendants in federal courts around the country. As later revealed by Judge Connolly, the subsequent litigation would be run through a “consulting” arm of IP Edge, MAVEXAR LLC, that is controlled by the firm’s three principals (attorneys Gautham (“Gau”) Bodepudi, Sanjay Pant, and Lillian Woung). Taken together, those LLC plaintiffs made IP Edge the most prolific NPE plaintiff, by an order of magnitude, for multiple years leading into and through 2022.

Judge Connolly became aware of this strategy as a result of the failure of several IP Edge plaintiffs—including Lamplight Licensing LLC, Mellaconic IP LLC, and Nimitz Technologies LLC—to comply with a pair of April 2022 standing orders requiring certain litigants to make certain detailed corporate and third-party litigation funding disclosures. He then ordered their individual owners, and some of their attorneys, to attend a pair of evidentiary hearings in early November 2022. Those hearings left Judge Connolly with systemic concerns regarding IP Edge’s assertion model: that by assigning patents to associated plaintiff LLCs without disclosing their connections to IP Edge and MAVEXAR, those two entities had perpetrated a fraud on the USPTO and/or the district court. The hearings also raised questions about the “accuracy of statements” made in the plaintiffs’ filed disclosures, in addition to concerns over “whether the real parties of interest are before the Court”. As a result, Judge Connolly handed down a series of extraordinarily sweeping orders requiring production to the court of a range of documents related to the plaintiffs’ legal representation, corporate ownership and control, assets, and potential liabilities. The ensuing “Series of Extraordinary Events” further snowballed to include multiple unsuccessful mandamus challenges contesting those production orders on various bases, as well as document production by those plaintiffs that turned out to be incomplete in certain respects.

On November 27, 2023, Judge Connolly issued an order that detailed the results of his investigation across 105 blistering pages—finding that IP Edge had been the “de facto” owner of the patents asserted by its litigating affiliates and held that the entity and its principals should face “consequences” for their improper attempt to “use separate LLCs to insulate themselves” from liability. He called upon the Department of Justice (DOJ) and the USPTO to potentially investigate these misrepresentations. As indicated above, Judge Connolly also teed up potential punishment for some of the individuals involved: He referred certain attorneys employed by IP Edge (which is not a law firm) to a Texas disciplinary body for the unauthorized practice of law and referred the LLCs’ local and lead counsel to state disciplinary bodies for improperly treating IP Edge as their true client.

Among the plaintiffs’ counsel hit with such a referral was Jimmy Chong, flagged over his conduct as Delaware counsel for Lamplight and Mellaconic IP. Judge Connolly flagged a variety of issues with his representation of both entities—including the fact that Chong obtained signed engagement letters from the clients (indirectly, via MAVEXAR), filed litigation on their behalf, and settled some of their cases without having ever communicated with their sole owners and managing members (Mellaconic’s Hao Bui, otherwise a food truck owner; and Lamplight’s Sally Pugal, otherwise a manager at a medical office).

Judge Connolly found that Chong (and, to varying degrees, the other plaintiff attorneys named in the order) had committed multiple violations of the rules governing the professional conduct of attorneys through that lack of communications. In particular, the court found that Chong had failed to secure the informed consent of his two clients, especially with regard to decisions related to filing, settling, and/or dismissing their cases. Judge Connolly also held that Chong and the other plaintiffs’ counsel had improperly delegated their fiduciary duties to MAVEXAR, finding that any supposed consent provided in their engagement letters was illusory, and that the issue was “especially concerning” given the “obvious disparity in the sophistication” of the plaintiffs (i.e., their owners)—as a result of which, the MAVEXAR consulting agreements “and counsel's actions in these cases deprived the LLC plaintiffs of the benefit of independent counsel”. This was further evident, per Judge Connolly, through the lopsided financial relationships between the plaintiffs and MAVEXAR, which appears to be entitled to 90% or more of each plaintiff’s settlement proceeds. Judge Connolly wasted no time in sending referral letters to the relevant disciplinary agencies for the attorneys named in the order—sending one to the Delaware Office of Disciplinary Counsel (ODC) with respect to the conduct of both Chong and George Pazuniak of O’Kelly & O’Rourke, LLC (counsel for Nimitz).

A subsequent set of orders in certain cases filed by Swirlate IP LLC and Waverly Licensing LLC, both also represented by Chong, indicated that his problems were far from over. On December 28, Judge Connolly ordered Chong and Bennett (Chong’s cocounsel in the Swirlate litigation) to appear in person on January 17, warning that both attorneys must be “prepared to address the Court’s concern” that the “same improprieties” prompting the referrals “may have occurred in connection with the litigation” filed by those two additional plaintiffs.

Judge Connolly held that hearing as scheduled for both Swirlate and Waverly, with both attorneys appearing as ordered. A full transcript is available here.

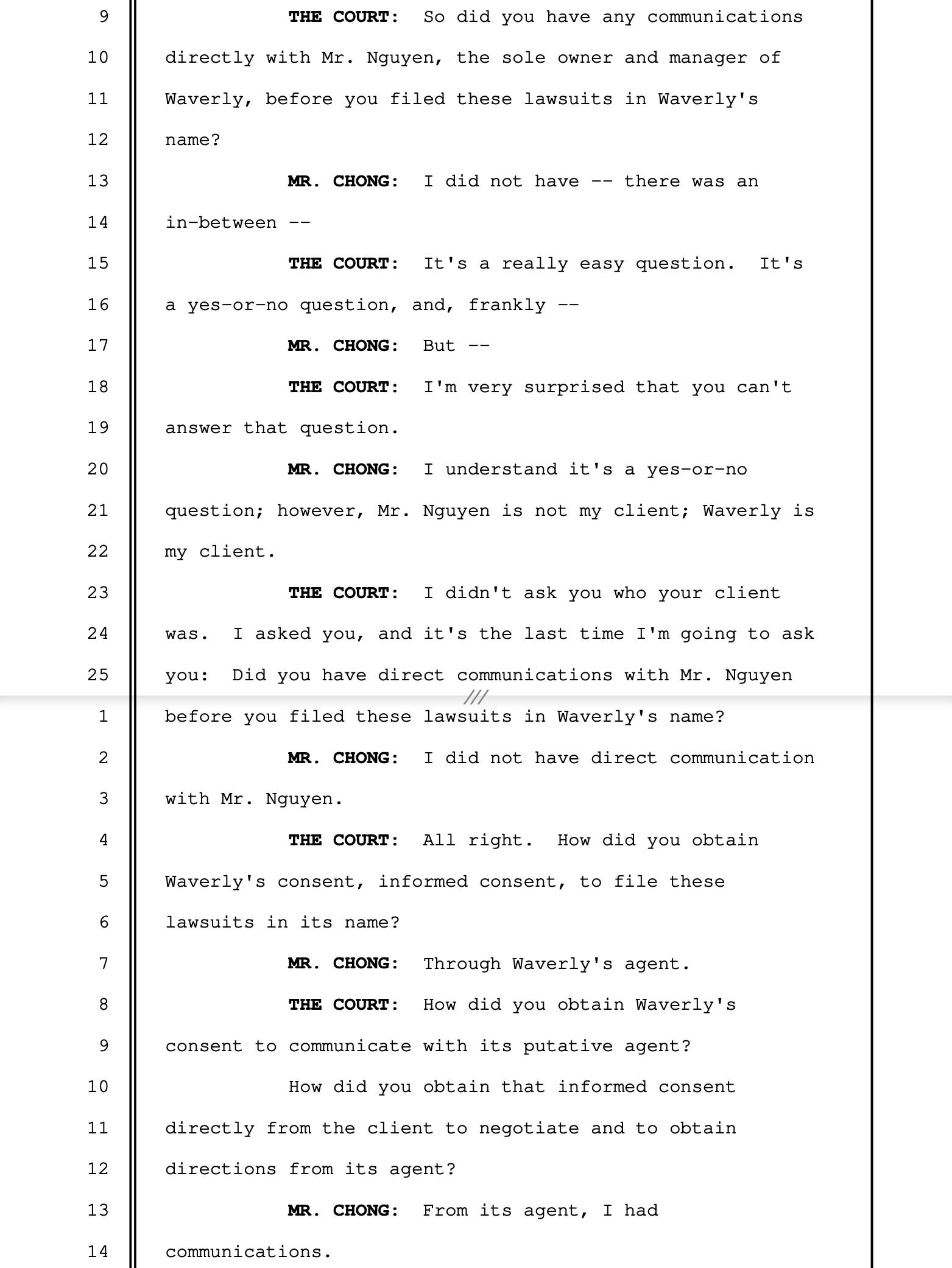

Beginning with Chong, Judge Connolly’s questioning over his representation of Waverly got testy rather quickly. Right out of the gate, when Judge Connolly asked whether he had communicated directly with the plaintiff’s owner, Son Nyugen, prior to filing suit, Chong attempted to frame his answer around having communicated with Waverly, characterizing the signing of a retainer agreement obtained via MAVEXAR (here described as Waverly’s “agent”) as constituting such communications. After Judge Connolly repeatedly asked him to address his communications with Nguyen, only to have Chong keep responding that he had done so with Waverly, Judge Connolly grew impatient—with Chong finally responding that no, he had not communicated with Nguyen before signing his engagement and filing suit:

This was apparently enough for Judge Connolly to conclude that Chong’s conduct had included similar ethical violations as in the Lamplight and Mellaconic cases, sufficient to warrant another referral to the Delaware ODC (the applicable disciplinary body).

I’ve already referred you to the Delaware Bar Disciplinary Counsel. I’m going to do so here because our rules require that you obtain the informed consent from the client in order for you to engage and rely on these negotiations -- I should say directions from a third party.

Chong then objected to the discussion of this new referral in open court, arguing that under Rule 13 of the “Delaware Disciplinary Rule” (apparently, referring to the Delaware Lawyers’ Rules of Disciplinary Procedure), there needs to be “confidentiality through these hearings”. Judge Connolly asked how that could possibly impact the hearing then in progress and pointed out that he had not yet referred Chong to the ODC, just that he was “going to do so”. Rather, Judge Connolly stated that his purpose in discussing the matter here was just to confirm whether Chong had communicated directly with Waverly (via Nguyen) before filing suit, with any additional commentary from Chong welcome but unnecessary:

The sole purpose right now is for me to ascertain whether or not you had direct communications with Waverly before you filed the lawsuit. And the answer you are telling me is no. And I’m telling you that . . . Therefore, I am going to refer you to disciplinary counsel. And I don’t actually need to have you answer any other questions, but you are welcome to, if you want to. But that suffices, in as far as your appearance here in the Waverly cases. That’s all I needed to ascertain.

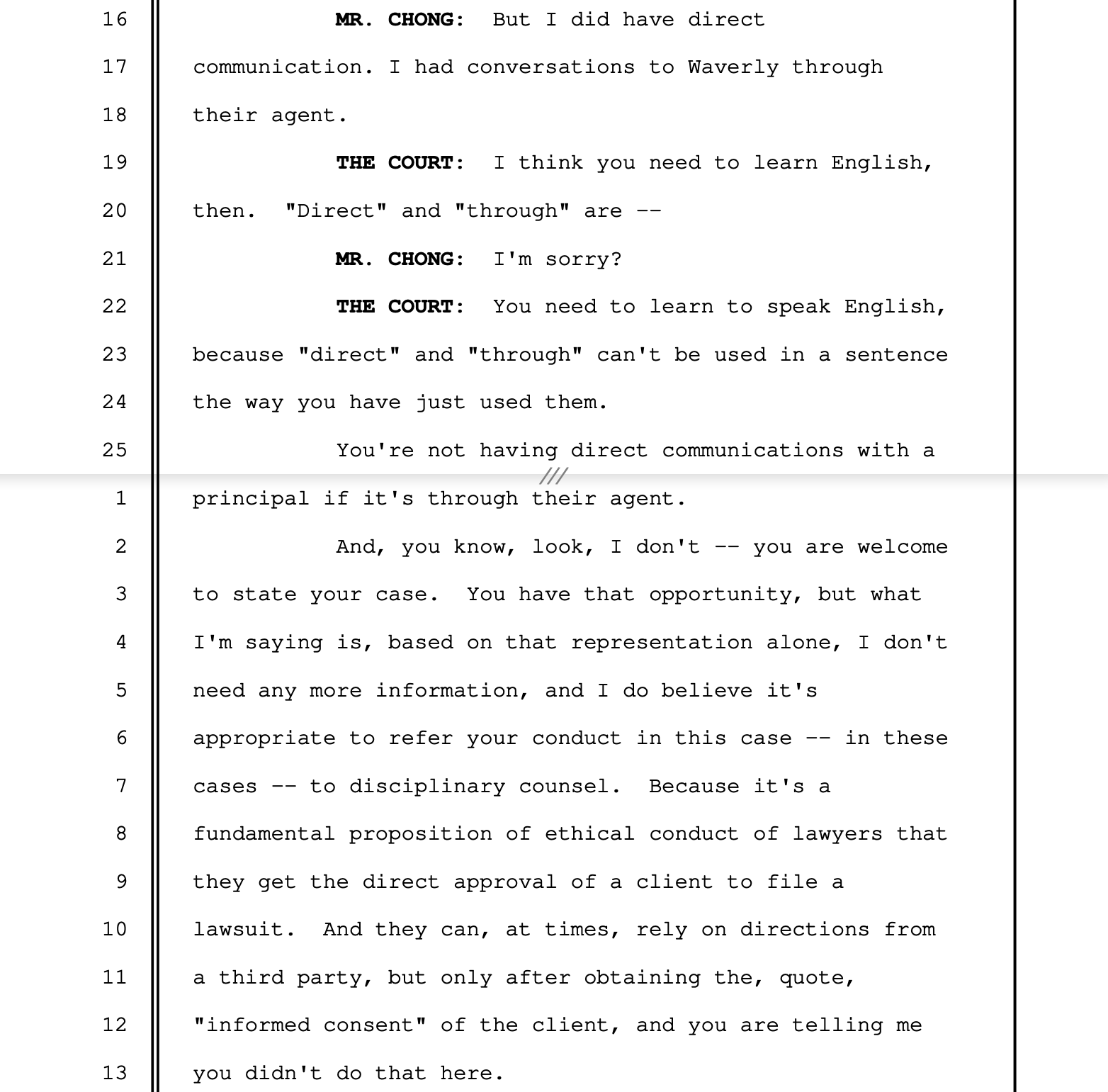

When Chong attempted once more to relitigate the “direct communications” issue, Judge Connolly appeared to lose his patience further—questioning both his command of the English language and his knowledge of the ethical rules he had already been found to violate:

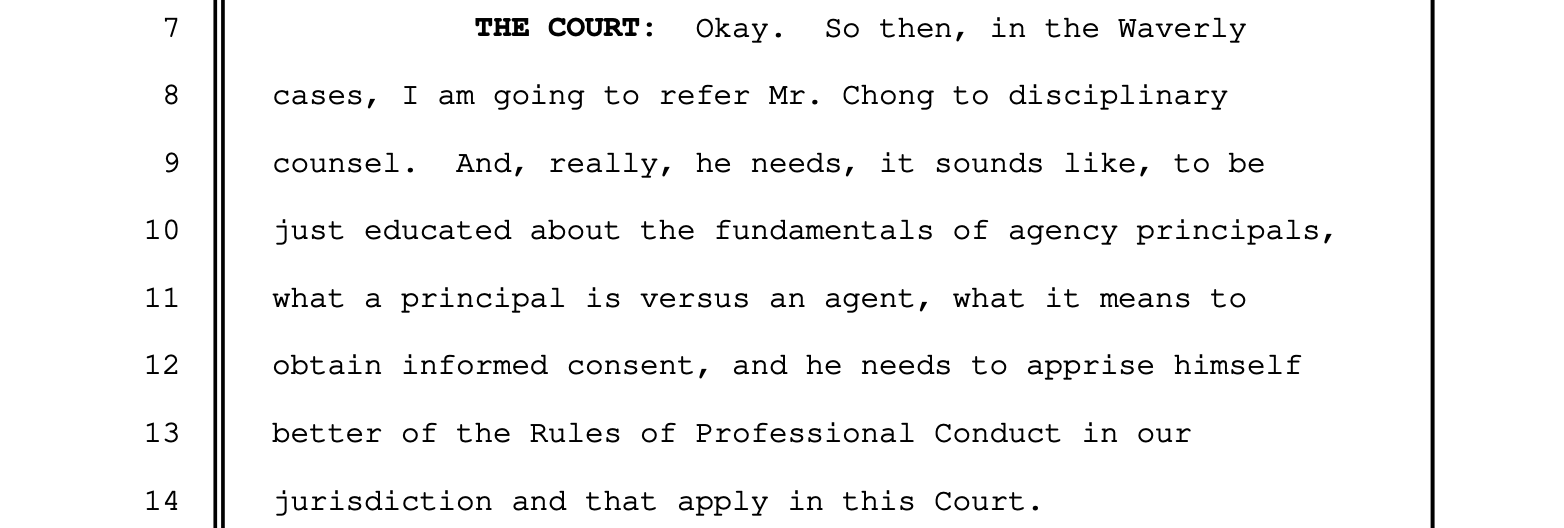

Following yet another back-and-forth in which Chong tripled down on the same argument, to which Judge Connolly again pointed out that communications through an agent cannot be direct by definition, he reiterated his decision to refer the matter to ODC—remarking that Chong could clearly use a refresher on the relevant principles:

Judge Connolly then turned to Swirlate, similarly asking Chong whether he had any direct communications with the plaintiff’s owner and sole employee, Dina Gamez. Here, though Chong explained that as local counsel, he relied on lead counsel Bennett to communicate with the client, and that he obtained his engagement agreement through Bennett.

Bennett then found himself in the hot seat, at which point he professed a lack of knowledge in response to various table-setting questions from Judge Connolly. In particular, Bennett claimed not to be familiar with the Nimitz, Backertop, and Mellaconic cases, though he later admitted to having read the November 2023 Nimitz order (which extensively discusses those lawsuits) that Judge Connolly cited in the order compelling Bennett’s testimony. Judge Connolly next attempted to jog his memory with respect to emails in which Bennett and the counsel in those cases discussed how to respond to his various orders in late 2022 (evidentiary and otherwise). In each instance, Bennett contended that due to the passage of time, he only recalled “generally, but not specifically”, the events in those cases.

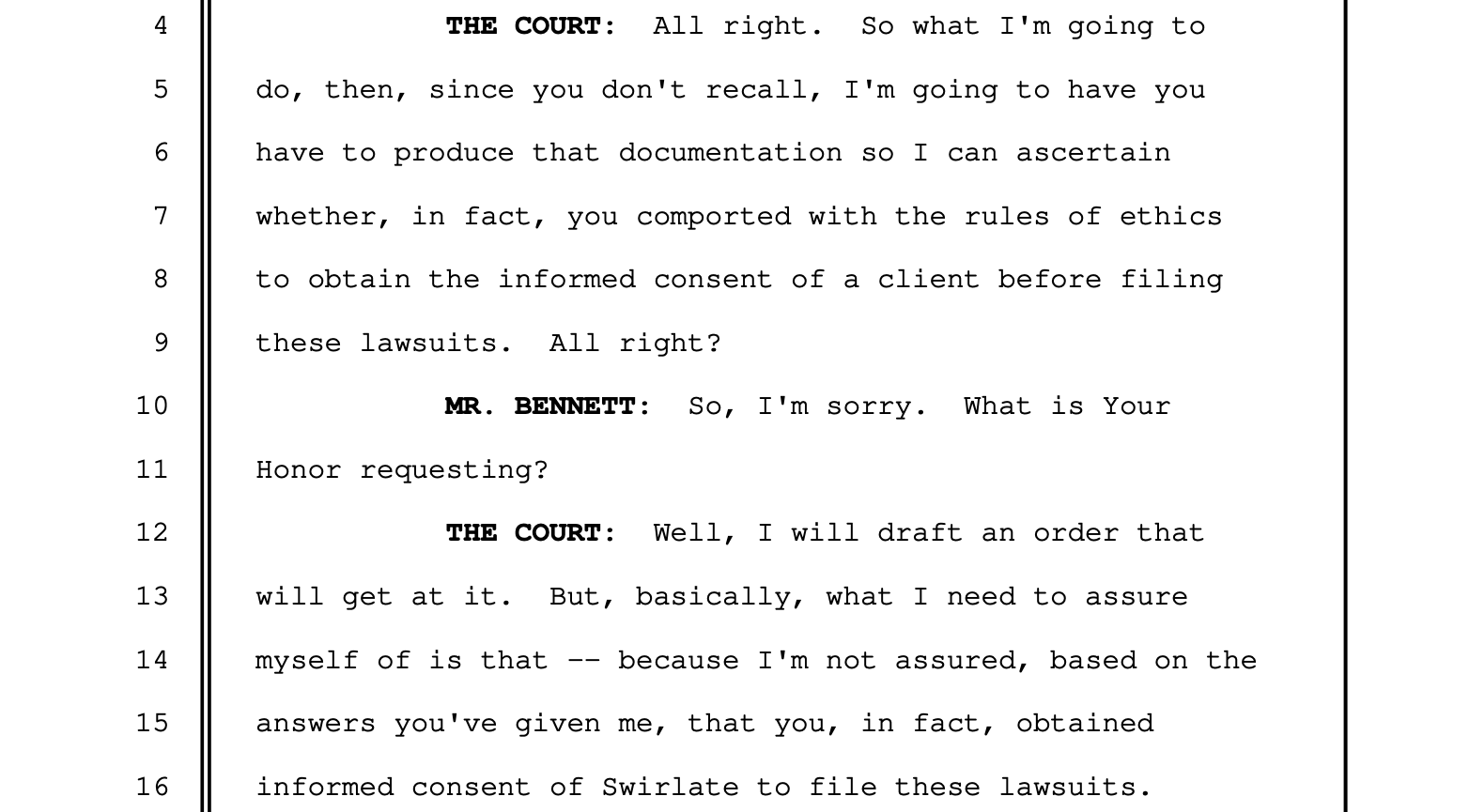

Judge Connolly then returned to his main line of inquiry, explaining that he wanted to ascertain whether Bennett, too, had failed to obtain the informed consent of his client, Swirlate (and, by extension, Gamez), to file and settle lawsuits on its behalf—as had formed the basis of his disciplinary referrals for Chong and the other counsel named in the November 2023 order. While Bennett similarly argued that he had received Gamez’s permission to file suit through an engagement agreement signed by her, he again claimed not to recall where the email through which he obtained that agreement came from. Rather, Bennett merely remarked that the relevant email chain would have included MAVEXAR as it was acting as her agent. Judge Connolly then asked whether Bennett had “relied exclusively on communications with Mavexar to take actions in these cases on behalf of Swirlate”; while Bennett responded in the negative, he also conceded that he had received Gamez’s supposedly informed consent “through [MAVEXAR]”. Nor, for that matter, could Bennett recall whether he had “communicated with Ms. Gamez in the first instance to obtain her informed consent”, as phrased by Judge Connolly, saying only that he would have to look back at his engagement agreement. (That said, as noted further below, Bennett would later suddenly remember more about those conversations.)

Judge Connolly responded by stating that he would issue another production order to fill in the gaps in Bennett’s apparently spotty memory as to whether he had complied with his ethical duties:

Bennett then appeared to express surprise and asked what rules he had broken—to which Judge Connolly reminded him that local rules require all attorneys appearing in the District of Delaware to comply with the Model Rules of Professional Conduct, which it would “appear [he violated . . . because [he] did not obtained the informed consent” of his client. Nor, said Judge Connolly, could he see how Bennett could not have violated those model rules if he “relied exclusively on the directions of Mavexar or IP Edge or a third party to file the lawsuit or to dismiss the lawsuit on its behalf”.

Bennett, unlike Chong, at least appeared to have prepared a substantive counterargument, arguing that certain Third Circuit cases supported his position that it was proper for MAVEXAR to communicate certain information as Swirlate’s agent. However, Judge Connolly was unmoved, reminding Bennett that the cited decisions presumed that the attorney had properly secured the client’s consent for such an arrangement in the first place: “[I]n order to get a client’s informed consent to take directions from a third party, you have to get the informed consent from the client”. Bennett also expressed confusion as to why Gamez, as its owner and managing partner, would not be considered another agent, asserting that a legal entity like Swirlate “could only communicate through their agents”. Judge Connolly, of course, disagreed: “No, actually, that’s not true. Swirlate has a natural person associated with it as all entities do. It’s got a sole owner and managing partner according to the disclosure that Swirlate filed with this Court, and that’s Dina Gamez”. After Bennett actually asked the court to remind him “who [he would] have to speak to in the client’s position” to obtain informed consent, Judge Connolly explained that it would be Gamez, as the only “natural person associated with the client”, who would be able to give such consent.

Bennett also attempted to secure a guarantee that all produced material would be kept confidential, prompting another incredulous response from Judge Connolly: “I can’t give you that guarantee, no. I can’t do that. I’ve never given—I don’t know of a Court that would ever do that”. In any event, Judge Connolly reminded Bennett that he could “short circuit” the whole production process if the attorney would look back through his files and just send a letter to confirm, as the court suspected, that he “never had communications directly with Dina Gamez to obtain the informed consent of Swirlate to file these lawsuits in its name, and instead . . . relied exclusively on communications with a third party, i.e., Mavexar or IP Edge”—given that the court would already, at that point, be “prepared to just refer [him] to the bar authorities in Illinois and let them do their job”.

Yet Bennett apparently preferred to try and relitigate his original point: that obtaining consent from MAVEXAR, as Swirlate’s agent, is the same as having received such consent from Swirlate itself. This prompted Judge Connolly to once again circle back to explain a key legal principle (and again, with an apparent tone of disbelief):

You can’t obtain informed consent of a principal to follow the directions of an agent through the agent. I mean, it just guts the whole definition of what informed consent of the principal means. It makes the rule and the requirement of informed consent to be absolutely meaningless. The whole point on the rule is to make sure that the client is giving the informed consent.

Judge Connolly then confirmed that he would move ahead with a production order, particularly in light of the fact that Bennett—in attempting to show that Swirlate’s consent had been effective—revealed, perhaps accidentally, that he had received verbal confirmation from Gamez that MAVEXAR “was working for her”. Remaining questions as to the timing of Bennett’s statements, as to whether he had had such communications before or after he filed the lawsuits, left enough ambiguity that the court found that it could not yet simply refer the matter to the Illinois disciplinary body as Bennett had requested. Indeed, Judge Connolly indicated that his own review of the materials to be produced was for Bennett’s own protection:

All right. So let’s find that out because I don’t want to refer you to the disciplinary authority if it turned out you got the informed consent. And because it also affects your good standing or whether you have good standing in this Court, it’s not something I can just, you know, punt.

Judge Connolly issued the promised production order on January 23, holding that Swirlate must produce to the court “no later than February 22, 2024 copies of the following documents and communications that are in the possession, custody, and control of Swirlate IP LLC, Dina Gamez, David R. Bennett, Direction IP Law, Jimmy Chong, and the Chong Law Firm”:

1) Any and all retention letters and/or agreements between Swirlate IP LLC and Direction IP Law or the Chong Law Firm.

2) Any and all communications and correspondence, including emails and text messages, that Dina Gamez had with David R. Bennett, Direction IP Law, Jimmy Chong, the Chong Law Firm, Mavexar LLC, IP Edge LLC, Linh Deitz, Papool Chaudhari, and/or any representative ofMavexar LLC and/or IP Edge LLC regarding:

a) The formation of Swirlate IP LLC;

b) Assets, including patents, owned by Swirlate IP LLC;

c) The potential acquisition of assets, including patents, by Swirlate IP LLC;

d) The nature, scope, and likelihood of any liability, including but not limited to attorney fees, expenses, and litigation costs, Swirlate IP LLC could incur as a result of its acquisition of and/or assertion in litigation of any patent;

e) U.S. Patent Nos. 7,154,961 and 7,567,622;

f) The retention of Direction IP Law and the Chong Law Firm to represent Swirlate IP LLC in these cases;

g) The settlement or potential settlement of these cases;

h) The dismissal of these cases; and

i) The cancelled December 6, 2022 hearing.

3) Any and all communications and correspondence, including emails and text messages, that David R. Bennett, Jimmy Chong, or any employee or representative of Direction IP Law or The Chong Law Firm had with Mavexar LLC, IP Edge LLC, Linh Dietz, Papool Chaudhari, and/or any representative of Mavexar LLC and/or IP Edge LLC regarding:

a) The formation of Swirlate IP LLC;

b) Assets, including patents, owned by Swirlate IP LLC;

c) The potential acquisition of assets, including patents, by Swirlate IP LLC;

d) The nature, scope, and likelihood of any liability, including but not limited to attorney fees, expenses, and litigation costs, Swirlate IP LLC could incur as a result of its acquisition of and/or assertion in litigation of any patent;

e) U.S. Patent Nos. 7,154,961 and 7,567,622;

f) The retention of Direction IP Law and the Chong Law Firm to represent Swirlate IP LLC in these cases;

g) The settlement or potential settlement of these cases;

h) The cancelled December 6, 2022 hearing

The order is similar in scope to those issued against other IP Edge plaintiffs involved in this saga—apart from the reference to the December 6, 2022 evidentiary hearing, which Chong, Bennett, and Gamez had been ordered to attend in person. Judge Connolly canceled that hearing after he stayed the Swirlate cases in light of the Federal Circuit’s own stay in the Nimitz litigation. While the Federal Circuit lifted the latter stay on December 8, 2022, Judge Connolly does not appear to have ever lifted the Swirlate stay, and he did not reschedule the evidentiary hearing (at least, with respect to securing testimony from Gamez).

For a blow-by-blow of the November 2022 evidentiary hearing that kicked this whole saga into high gear, see “Recent Delaware Evidentiary Hearings Characterized as ‘Perverse Prying’ by a ‘Lone-Wolf Prosecutor’ Were Wide-Ranging” (November 2022). A deep dive on the recent order in which Judge Connolly laid out the results of his investigation can also be found here: “Judge Connolly Refers IP Edge ‘Fraud’ Saga to DOJ, USPTO, and State Disciplinary Bodies” (December 2023).

Editor’s Note: This article was updated after publication to reflect the contents of the production order issued against Swirlate IP.