PTAB May Consider Alice in IPR Claim Amendments, Holds Split Federal Circuit Panel

Patent validity challenges filed with the Patent Trial and Appeal Board are usually limited in scope, with inter partes review (IPR) petitions restricted to grounds based on Section 102 and 103. Alice, meanwhile, can be invoked only in petitions for covered business method (CBM) review and post-grant review, which may only consider a subset of patents. However, Section 101 has also come into play for IPRs during the claim amendment process, since when patent owners seek to amend their claims in an IPR, the Board’s practice has been to evaluate the subject matter eligibility of the proposed new or amended claims. A split Federal Circuit has just signed off on this approach, holding in a 2-1 decision that the PTAB has the authority to do so—affirming a final decision in an IPR filed by Amazon, Hulu, and Netflix that invalidated claims from a patent held by Uniloc 2017 LLC and rejected a motion to amend under Alice. The decision came over an emphatic dissent from Circuit Judge Kathleen M. O’Malley, who argued that the Board cannot apply Section 101 in IPRs.

IPR petitioners Amazon, Hulu, and Netflix are among several defendants accused of infringing the challenged patent (8,566,960) by two subsidiaries of Australian Uniloc Corporation Pty. Limited, which sued the three companies in May 2016 over the provision of streaming services. (The ‘960 patent, which generally relates to limiting access to a software product to a certain number of devices, is among numerous assets that Uniloc subsequently assigned in May 2018 to Uniloc 2017, a subsidiary of Fortress Investment Group LLC, as part of a deal in which Fortress apparently took over Uniloc’s assertion strategy. See here for a detailed overview of that history.) Those three defendants challenged the validity of the ‘960 patent under Alice, leading to the dismissal of the cases against them in March 2017 by District Judge Robert W. Schroeder III. Judge Schroeder ruled that the ‘960 patent is invalid under Alice as directed to the abstract idea of a “time-adjustable license”, explaining that this “is an abstract idea because licensing is a fundamental economic practice and because licenses are abstract exchanges of intangible contractual obligations” and concluding that the patent lacks an inventive concept. The Federal Circuit summarily affirmed that decision in August 2018.

Meanwhile, the defendants also filed the IPR here at issue (IPR2017-00948) in February 2017, a month before the district court granted dismissal under Alice. The following January, Uniloc filed a contingent motion to amend, offering proposed substitutes for independent claims 1, 22, and 25 in the event that the claims were invalidated. Amazon, Hulu, and Netflix challenged the eligibility of the proposed new claims under Alice in their opposition to that motion, noting the district court ruling that had invalidated the claims under Alice and arguing that the motion to amend “did nothing to address the patent-eligibility problems underlying that judgment”, adding that “the substitute claims suffer the same deficiencies”. Uniloc asserted in response that the petitioners could not raise Alice in a motion to amend. However, the PTAB nonetheless denied Uniloc’s motion to amend in its August 2018 final written decision, solely on the basis of Alice, also cancelling the challenged original claims on the petitioned grounds.

In January 2019, the Board then declined to revisit that decision in denying Uniloc’s motion for a rehearing, holding that the PTAB may consider patent eligibility when determining the patentability of proposed substitute claims in IPR proceedings. Uniloc appealed that decision to the Federal Circuit that same March.

The Panel Spars Over the Merits: Do the IPR Statutes Allow the Alice Analysis for Claim Amendments?

The Majority: The PTAB Does Have this Authority Under Section 311(b)

The Federal Circuit ruled on appeal on July 22, 2020, with Circuit Judge Evan J. Wallach writing for the majority and joined by Circuit Judge Richard G. Taranto. The majority held that the PTAB had correctly concluded that it is not limited in its review of proposed substitute claims by Section 311(b) (which establishes that a petitioner “may request to cancel” claims only under 102 and 103) and that it has the authority to consider Section 101 eligibility in this context. This conclusion, the majority held, is “supported by the text, structure, and history of the IPR Statutes, which indicate Congress’s unambiguous intent to permit the PTAB to review proposed substitute claims more broadly than those bases provided in § 311(b).” The IPR statutes “plainly and repeatedly require” the Board to consider the “patentability” of claims, explained the majority, and a Section 101 analysis is a patentability determination. “The plain language of the IPR Statutes demonstrates Congress’s intent for the PTAB to review proposed substitute claims for overall ‘patentability’—including under § 101—of the claims.” Section 311(b) does not change this conclusion, continued the majority, as it “is confined to the review of existing patent claims, not proposed ones”. The statutory language in that provision refers to the cancellation or annulment of claims, noted the majority. Under the ordinary meaning of that language, only claims that are in effect can be cancelled—and “[i]n an IPR, only the preexisting claims of the at-issue patent are in effect”.

This conclusion, the majority further argued, is supported both by the structure and legislative history of the IPR statutes. As to structure, the majority found it to be significant that the IPR statutes are organized chronologically according to how an IPR proceeds: “Section 311, as a provision applying to the petition phase of the proceedings, should not therefore bind a separate adjudication-stage provision”. With respect to the legislative history, the majority found that “it was Congress’s intent to permit the PTAB to address issues that ‘have escaped review at the time of the initial examination’”. Furthermore, “[p]roposed substitute claims in an IPR proceeding have not undergone a patentability review by the USPTO, see 35 U.S.C. § 316, and so the ‘substantial new questions of patentability’ that ‘have not previously been considered by the [US]PTO’”—questions central to reexamination and that apply equally to IPR, argued the majority, extending its 2011 In re: NTP holding—“include all patentability questions, including § 101 patent eligibility”. As noted by the USPTO in its brief in intervention, the majority underscored that allowing the issuance of claims that have not been evaluated under Section 101 (as well as Section 112) would allow patent owners seeking amendment to “overcome prior art and obtain new claims simply by going outside the boundaries of patent eligibility and the invention described in the specification”, thereby “allowing patents with otherwise invalidated claims ‘to return from the dead as IPR amendments’” (citing the USPTO’s brief).

Judge O’Malley’s Dissent: The PTAB Lacks the Authority to Consider Alice for Claim Amendments

Judge O’Malley dissented and rejected the majority’s holding on the merits, characterizing it as ruling that “when it comes to substitute claims, the Board can engage in a full-blown examination”—and dismissing this “revelation” as one that “runs contrary to the plain language of the statute and the policy of efficiency that underlies the IPR system”. Judge O’Malley states that the majority’s interpretation of the IPR statutes focuses too “narrowly” on the text of Sections 311, 316, and 318 and “fails entirely to contend with the clear framework of the IPR provisions. Plain language interpretation requires more than cherry picking provisions out of context”.

In particular, Judge O’Malley objected to the majority’s position that “patentability . . . means one thing as to ‘any patent claim challenged by the petitioner’ and something entirely different as to ‘any new claim added under section 316(d)’”, arguing that ascribing two different meanings to the same term runs counter to the basic principles of statutory interpretation. Irrespective of how the term “patentability” is used in Section 101, it should be defined as it is used in the statutes here at issue—and in that context, Judge O’Malley argued, “[t]he sole meaning of patentability must be . . . the one contemplated by § 311(b)” as to challenged claims.

Furthermore, Judge O’Malley rejected the majority’s argument that Congress did not intend for Section 311 to place limits on the consideration of substitute claims, faulting that position as being based solely on a parsing of the statutory language and not on a review of the legislative history. Rather, “[l]ooking at the statutory framework as a whole, ‘[t]he structure of an IPR does not allow the patent owner to inject a wholly new proposition of unpatentability into the IPR by proposing an amended claim’” (citing the Federal Circuit’s Aqua Products decision, rejected as inapplicable by the majority). It is this limit placed on the petitioner that should determine the scope of the IPR regime, argued Judge O’Malley: in contrast to the majority’s conclusion, the overall structure of the IPR regime indicates that “Congress intended to limit the Board’s authority to a review of the specified patentability grounds” (emphasis added). To the extent that the chronological structure of the IPR statutes is relevant, Judge O’Malley continued, it further supports this point: since “[s]ubstitute claims come into existence only after the scope of the IPR has been set”, “[i]t follows that Congress did not need to rearticulate a parameter already expressed in prior provisions: IPRs are limited to §§ 102 or 103 and to prior art consisting of patents or printed publications”. This reading is further supported by the fact that “Congress failed to describe separate standards for evaluating challenged claims and substitute claims”. Judge O’Malley then proceeded to rebut the majority’s interpretation of certain caselaw—in part, criticizing it for stating that the Aqua Products plurality opinion was directed solely to “whether a petitioner challenging the proposed substitute claims bears § 316(e)’s burden of proof”, which in the judge’s view improperly minimized the “significance” of the opinion.

Taking a step back, Judge O’Malley then faulted the majority’s core holding—characterizing it as standing for the notion “that, when it comes to substitute claims, anything goes”—as “contrary to the policy supporting the IPR system”. Rather, Judge O’Malley argues, “IPRs are meant to be an efficient, cost-effective means for adjudicating patent validity . . . They are not intended to also serve as a means for full-blown examination”, a position allegedly consistent with the relevant legislative history. The majority holding will place additional weight on an already overburdened process by “open[ing] substitute claims to an examination equivalent to that undertaken during patent prosecution, in an inter partes environment”—“improperly” placing this task in the hands of an Administrative Patent Judge rather than an examiner.

While “[t]he Board can cancel claims and find proposed substitute claims unpatentable”, Judge O’Malley summarized in conclusion, “[i]t simply does not have statutory authority to do so based on § 101”.

The Panel Debates Mootness: Was the Case “Dead on Arrival”?

The Majority: The Case Was Not Moot—and Such an Argument Had Been Waived

In addition to its debate over the merits, the majority and minority also sparred over the threshold issue of whether the appeal was moot. The majority arguing that it was not, as the Federal Circuit would have been able to grant relief to Uniloc, in the form of a certificate adding its amended claims, if it were to have prevailed. To that end, the majority rejected arguments to the contrary from Hulu, which had argued that the motion to amend was not made “during the IPR” since it was contingent on the Board not cancelling the original claims, a decision that it asserted had ended the IPR. The Federal Circuit further declined to accept arguments that the appeal was mooted by the district court’s opinion invalidating the patent under Alice. Beyond its substantive rejection of those arguments, the appeals court held, the petitioner had waived them by not first raising them before the PTAB—holding that “[a] question of an agency’s statutory authorization ordinarily is not a nonwaivable ‘jurisdictional’ issue”. The majority also disagreed with the dissenting Judge O’Malley’s interpretation of the word “substitute” in 35 USC Section 316(d) (governing IPR claim amendments) as making it so that no substitute claim can issue if the original is invalidated—rejecting the dissent’s premise “that the patentee must give what amounts to consideration—something of value—to obtain a replacement claim”.

The Dissent: The District Court’s Alice Ruling Makes Claim Amendments a Dead Issue

Judge O’Malley disagreed, arguing instead that the case was indeed moot—asserting that “[i]n this case, relief is possible only if, in the event of a remand, the Board has authority to issue substitute claims” (emphasis in original). However, “[c]ompleting such a substitution requires that there be original claims to substitute out for the new claims—i.e., in the words of the Patent Office itself, the patentee must ‘replace’ a challenged claim with a substitute”. This was not the case here, continued Judge O’Malley: since the district court had invalidated the patent at issue under Alice, and because the Federal Circuit affirmed that ruling and Uniloc had not sought Supreme Court review of that affirmance, the NPE no longer possessed “any patent rights that it could give up in exchange for a substitute claim. It owned nothing and could not, therefore, substitute its old claims for new ones”. As a result, should Uniloc prevail on appeal and get the IPR decision remanded to the PTAB, “the Board would be without power to effectuate a substitution. The finality of our invalidity judgment should therefore be the end of the inquiry in this case”.

Relatedly, Judge O’Malley also rejected the majority’s holding that “[a] question of an agency’s statutory authorization ordinarily is not a nonwaivable ‘jurisdictional’ issue”, arguing that “[b]ecause mootness implicates Article III’s case or controversy requirement—a threshold jurisdictional issue—a party cannot waive it”. Moreover, Judge O’Malley asserted that the nonwaivable issue of jurisdiction is separate from a waivable “challenge to an agency’s authority”.

Judge O’Malley then returned to the issue of mootness as she summed up her critique of the majority’s merits holding—underscoring that the case was “dead on arrival” and faulting the majority for “declar[ing] that dead patents can walk, at least as far as needed to die again on the same § 101 sword that killed [the patent-in-suit] two years ago. That sword, however, does not exist in the IPR context”.

The Overall Narrower State of Alice

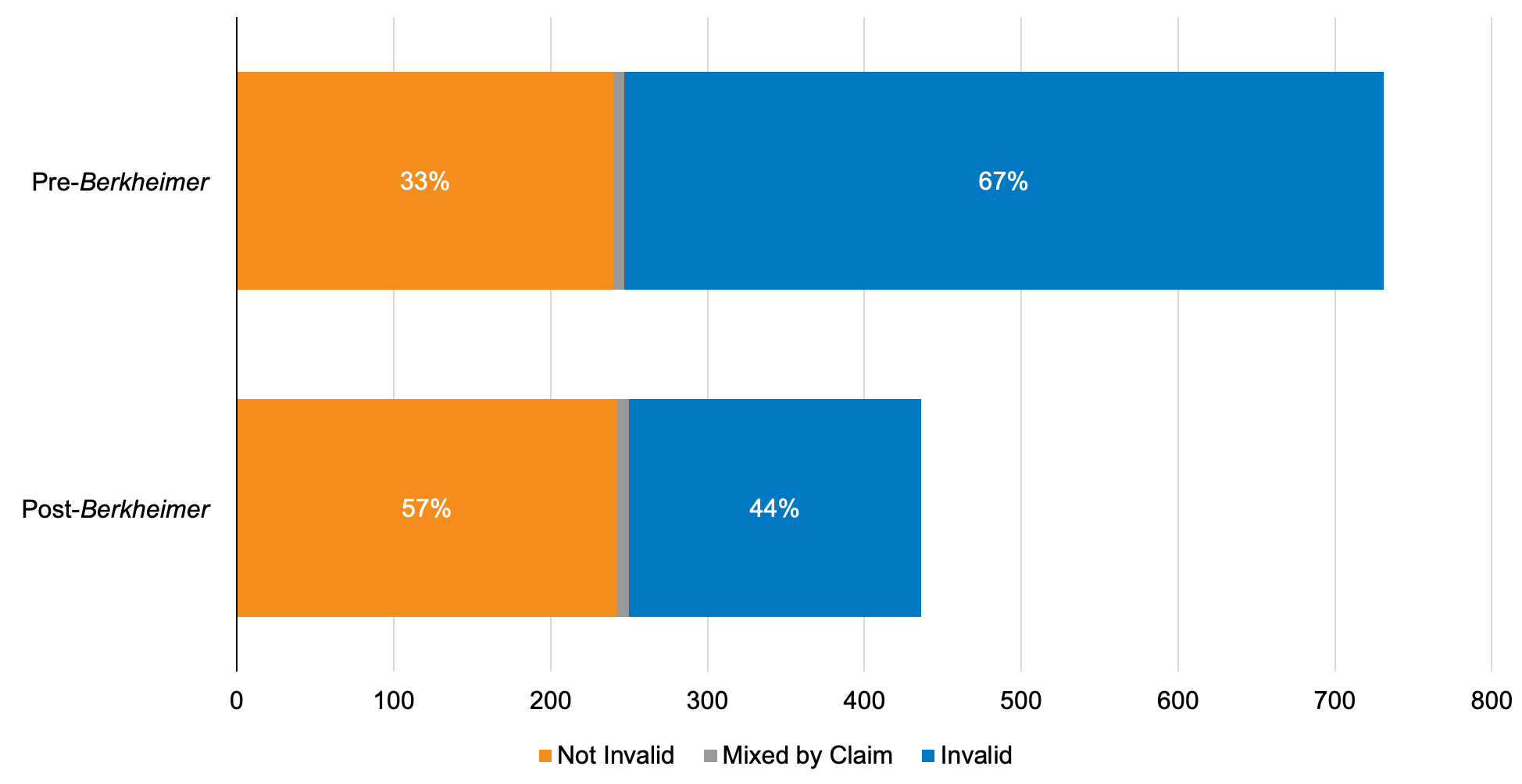

The Federal Circuit’s Uniloc decision stands out against a body of caselaw from the appeals court that has tended to reduce the circumstances in which defendants can leverage Alice. Indeed, as covered extensively by RPX, the court’s February 2018 decisions in Berkheimer and Aatrix have made it much harder for defendants to win early dismissal under Alice through their holding that factual disputes may preclude early dismissal under Section 101. The result has been a dramatic drop in Alice invalidations: while 67% of the patents challenged and adjudicated before Berkheimer had all claims at issue cancelled, that has dropped to 44% for those decided since.

Patents Invalidated Under Alice Before and After Berkheimer

However, RPX’s analysis indicates that not all plaintiff types fare the same when trying to use Berkheimer to avoid facing Alice. Rather, NPEs tend to do quite a bit worse.

For more on this and other trends affecting Alice and a variety of other important issues impacting patent litigation, see RPX’s second-quarter review.