Solicitor General Pushes Supreme Court to Revisit Section 101 in American Axle

Since the US Supreme Court’s June 2014 Alice opinion, courts have struggled to consistently apply its two-part test for determining patent eligibility under Section 101. That includes the Federal Circuit, which in recent years has become split over the extent to which Alice should be applied for mechanical inventions. One such ruling—the court’s divided opinion in American Axle Manufacturing v. Neapco—could soon lead the Supreme Court to finally revisit Alice. On May 19, more than a year after the Court issued a Call for the Views of the Solicitor General (CVSG) in the American Axle appeal, US Solicitor General Elizabeth B. Prelogar filed a brief on behalf of the government recommending that certoriari be granted in part, a step that greatly increases the chances that the Court will move forward, at least according to a recent empirical analysis. Data on district court eligibility challenges, meanwhile, reflect how subsequent Federal Circuit rulings have blunted Alice’s impact.

Readers already familiar with the twists and turns of the American Axle litigation may wish to proceed to the overview below of the Solicitor General’s brief. Regardless, given the complexity of the issues at play in American Axle, a recap of that history provides useful context for the issues currently before the Supreme Court—and underscores the sharp Federal Circuit split on the bounds of Section 101 caselaw.

– Data Update: Alice Remains in Narrowed State Post-Berkheimer

– The Litigation Below: An Increasingly Divided Federal Circuit

– The Solicitor General’s Brief: The Federal Circuit Got It Wrong

– What Comes Next: Likelihood of Supreme Court Review

Data Update: Alice Remains in Narrowed State Post-Berkheimer

The Supreme Court’s potential return to the arena of Section 101 comes as Alice remains a less readily available defense as a result of the Federal Circuit’s February 2018 rulings in Berkheimer v. HP and Aatrix Software v. Green Shades Software. In Berkheimer, the Federal Circuit held that factual disputes over a patent’s inventiveness may preclude courts from deciding motions for summary judgment on patent ineligibility, extending that holding shortly thereafter to motions brought under Rule 12 in Aatrix.

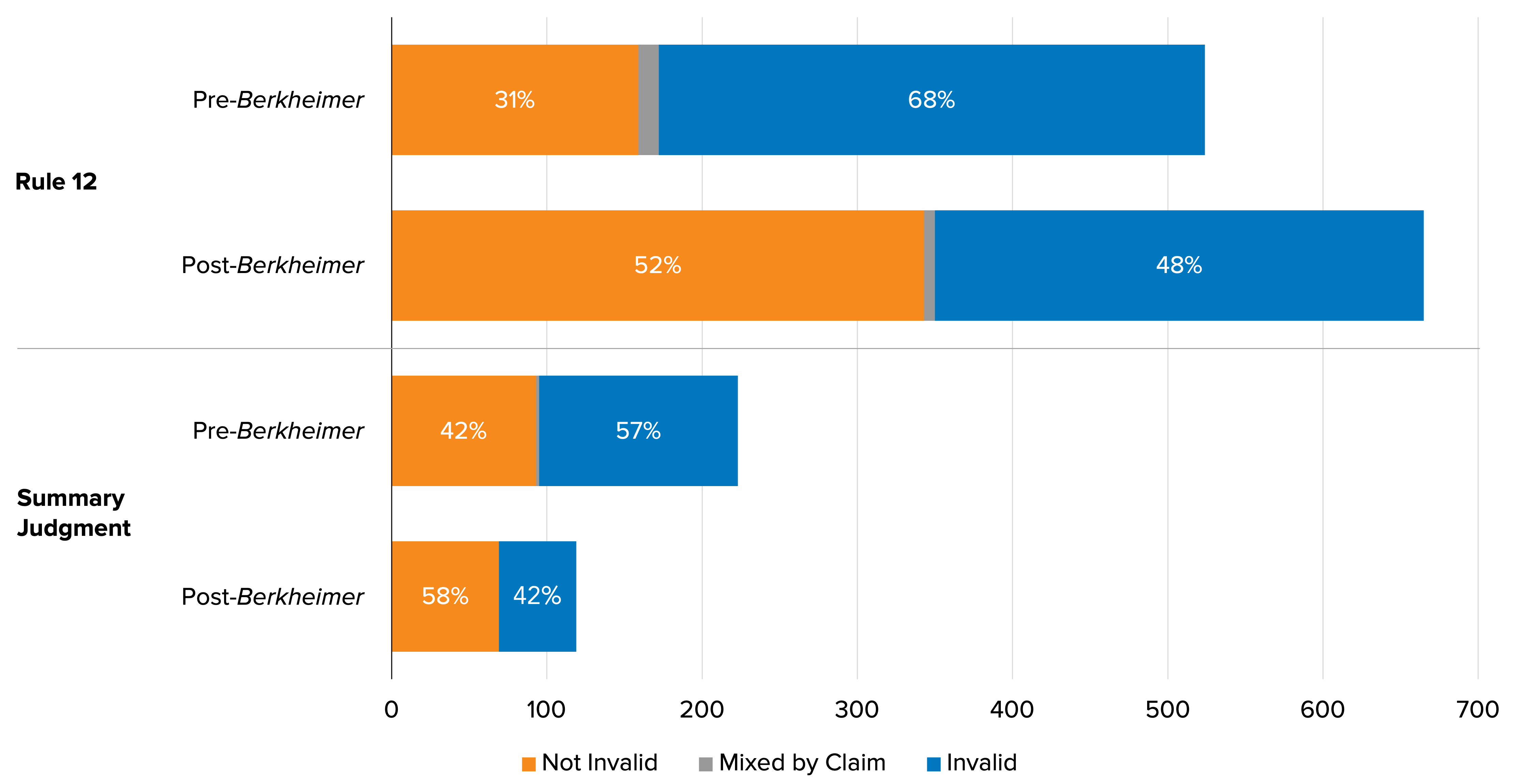

Post-Berkheimer, district courts are now far less likely to grant Alice motions at either stage. Although courts granted motions to dismiss under Rule 12 for 68% of patents with Alice challenges decided before Berkheimer, they have only invalidated 48% of the patents adjudicated at that stage since then. Additionally, the invalidation rate at summary judgment has dropped from 57% before Berkheimer to 42% since.

Patents Invalidated Under Alice by Procedural Stage, Pre-/Post-Berkheimer (District Court)

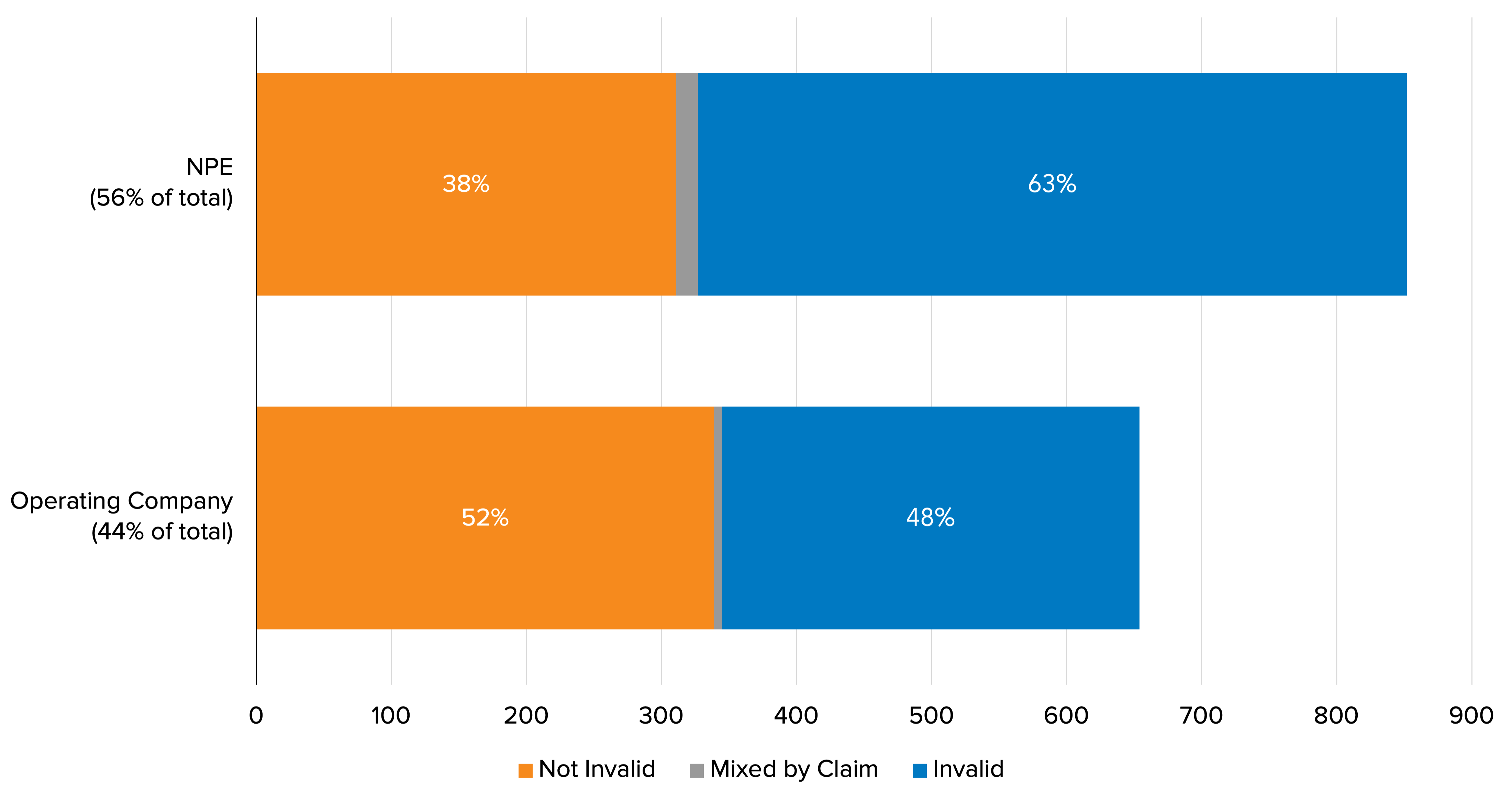

More broadly, a breakdown of the overall Alice invalidation rate by plaintiff type, with no limit by date, reveal that NPE-asserted patents challenged under the decision’s rationale have fared worse than those litigated by operating companies. Of the NPE patents adjudicated since Alice’s issuance, 63% had all challenged claims invalidated, compared to 48% for operating company patents.

Patents Invalidated Under Alice by Plaintiff Type (District Court)

The Litigation Below: An Increasingly Divided Federal Circuit

The patent at issue in American Axle (7,774,911) describes an automotive drive shaft that allegedly improves upon prior art techniques for resisting vibration—in particular, bending mode vibration (where energy is transmitted longitudinally along a shaft, causing it to bend at various points) and shell mode vibration (wherein a standing wave of energy is transmitted circumferentially about the shaft), both of which produce vibrations at different frequencies. The claimed drive shaft is hollow and incorporates a hollow liner that is tuned to produce its own vibration that attenuates, or dampens, both types of vibration, whereas prior art systems were allegedly unsuitable for doing so simultaneously.

Plaintiff American Axle Manufacturing (AAM) asserted the patent against competitor Neapco in December 2015. In February 2018, District Judge Leonard P. Stark granted the defendant’s summary judgment motion of patent ineligibility, ruling at Alice step one that the representative claims (independent claims 1 and 22) were directed to laws of nature—specifically, to Hooke’s law, an equation “that describes the relationship between an object’s mass, its stiffness, and the frequency at which the object vibrates” (as summarized by the Federal Circuit majority on appeal); and to friction damping, a type of damping that “occur[s] due to the resistive friction and interaction of two surfaces that press against each other as a source of energy dissipation” (per the district court). The claimed “additional steps”, Judge Stark held at step two, “consist of well-understood, routine, conventional activity already engaged in by the scientific community . . . and those steps, when viewed as a whole, add nothing significant beyond the sum of their parts taken separately”. As a result, Judge Stark held that the claimed system amounts to a “directive to use one’s knowledge of Hooke’s law, and possibly other natural laws, to engage in an ad hoc trial-and-error process of changing the characteristics of a liner until a desired result is achieved”.

The Original Federal Circuit Opinion

In the original October 2019 ruling on appeal, authored by Circuit Judge Timothy B. Dyk, a Federal Circuit majority essentially agreed with the district court. The majority acknowledged AAM’s arguments that the claimed invention involves more than just Hooke’s Law—specifically, that Hooke’s Law describes a spring with a single degree of freedom, whereas a liner has different stiffnesses in different directions, making the claimed system too complex to be described by Hooke’s Law. However, the majority ruled that the “problem with AAM’s argument is that the solution to these desired results is not claimed in the patent”, explaining that the claims do not specify how to change the necessary variables (described in the specification) “to produce the multiple frequencies required to achieve a dual-damping result, or to tune a liner to dampen bending mode vibrations”.

As a result, the majority ruled that the claims were ineligible for the same reason as those ruled unpatentable in Parker v. Flook, in which the Supreme Court invalidated claims related to setting alarm limits for a catalytic process by using a mathematical formula to, in part, identify temperature limits. In Flook, the court ruled the claims ineligible because they merely applied the formula in a certain context and did not specify how variables were measured, nor how the alarm system functioned—a lack of specificity also found here, the majority held. The added complexity cited by AAM, per the majority, was insufficient to make the claims patent eligible. “What is missing is any physical structure or steps for achieving the claimed result of damping two different types of vibrations”.

Judge Moore’s First Dissent

Circuit Judge Kimberly A. Moore dissented, arguing that the “majority’s decision expands § 101 well beyond its statutory gate-keeping function and the role of this appellate court well beyond its authority”. Judge Moore also faulted the majority for oversimplifying the Alice test by reducing it “to a single inquiry: If the claims are directed to a law of nature (even if the court cannot articulate the precise law of nature)”, a reference to general statements in the majority opinion that, for example, found the claims to be directed to “Hooke’s law and possibly other natural laws”.

Judge Moore also objected to what she characterized as the majority’s “disregard” for the second step of Alice, arguing that there are “many” inventive concepts described in the claims themselves that, at least, raised questions of fact regarding whether those additions were conventional and or routine—questions that “should have precluded summary judgment”. By dismissing the identified inventive concepts as making “no difference”, the majority was “outright rejecti[ng] . . .the second step of the Alice/Mayo test”.

Moreover, Judge Moore found the majority’s concerns about specifying the method of liner tuning to be fundamentally misplaced, arguing that this had nothing to do with the natural law inquiry under Section 101. Rather, Judge Moore argued that this was really a question of enablement, which should be addressed under Section 112. “We cannot convert § 101 into a panacea for every concern we have over an invention’s patentability, especially where the patent statute expressly addresses the other conditions of patentability and where the defendant has not challenged them”.

Judge Moore concluded by asserting that “Section 101 simply should not be this sweeping and this manipulatable” and should not encompass the same standards as other patentability rules—and in particular, should not “subsume” Section 112. “The majority’s validity goulash is troubling and inconsistent with the patent statute and precedent”.

The Federal Circuit’s En Banc Denial and Revised Opinion

The Federal Circuit became even more fractured in July 2020, splitting 6-6 over the patent owner’s petition for en banc rehearing—resulting in the petition’s denial. On the same day, the court also issued a modified majority opinion that maintained its original holding as to claim 22, again concluding that the claim failed at Alice step one for its failure to specify how the described “tuning” of the liner should occur. Here, though, the majority clarified that this holding “extends only where, as here, a claim on its face clearly invokes a natural law, and nothing more, to achieve a claimed result”.

However, the majority revisited its earlier conclusion with respect to claim 1, distinguishing it as more general than claim 22. While claim 22 describes “tuning a mass and a stiffness of at least one liner” (emphasis added), claim 1 referred more broadly to “tuning at least one liner to attenuate at least two types of vibration transmitted through the shaft member” (emphasis added), the latter highlighted portion construed by the district court as meaning “controlling characteristics of at least one liner”. The majority found that in light of the specification, these “characteristics” may include variables other than mass and stiffness, further noting that claim 1 (unlike claim 22) includes limitations related to “positioning” the liner. As a result, the majority held that it “cannot conclude that [claim 1] is merely directed to Hooke’s law”. Rather, it ruled that the district court opinion suggests that both the “broader concept of tuning” and the “broad concept of positioning” are both abstract ideas, remanding as to claim 1 for consideration of this “alternative eligibility theory”.

The majority also took the opportunity to push back against several of Judge Moore’s criticisms. These included two key broader disagreements on the applicable law. First, the majority disagreed with Judge Moore as to whether claims challenged under the natural law exception need to explicitly identify a natural law, stating that nothing in Mayo and other caselaw expressly requires such a citation—and that to require otherwise would make eligibility “depend upon the ‘draftsman’s art,’ the very approach that Mayo rejected”.

Second, the majority rejected Judge Moore’s position as to enablement, countering that Judge Moore had “fail[ed] to distinguish two different ‘how’ requirements in patent law”: the eligibility requirement, which requires that the claim itself “go beyond stating a functional result” in that “it must identify ‘how’ that functional result is achieved”; and the enablement requirement, which applies not to the claim but the specification, and requires that the specification “set forth enough information for a relevant skilled artisan to be able to make and use the claimed structures or perform the claimed actions”.

Judge Moore’s Second Dissent

Judge Moore also doubled down, reemphasizing her prior criticisms in a revised dissent, arguing that “[t]he majority creates a new test for when claims are directed to a natural law despite no natural law being recited in the claims, the Nothing More test” (emphasis in original).

The premise of this supposed test was fundamentally flawed, Judge Moore contended, in that it untenably treats a claim’s invocation of a natural law as meaning that the claim is “directed to” that law. This is inherently problematic, according to Judge Moore, because “[e]very mechanical invention requires use and application of the laws of physics. It cannot suffice to hold a claim directed to a natural law simply because compliance with a natural law is required to practice the method”. To interpret the natural law exception so expansively, per Judge Moore, was unacceptable: “Section 101 is monstrous enough, it cannot be that use of an unclaimed natural law in the performance of an industrial process is sufficient to hold the claims directed to that natural law”.

Judge Moore further criticized the majority for moving ahead with a de novo application of this “Nothing More” test, arguing that by ruling that claim 22 was directed to “Hooke’s law and nothing more”, it was ignoring evidence that the claim was in fact directed to “the combination of Hooke’s law and friction damping”—as the district court concluded, and even the defendant had argued. This was wrong in several respects, according to Judge Moore, including that the majority was treating this determination as a question of law when it should be a question of fact. The majority’s consideration of the extrinsic record on this point was also in error, continued Judge Moore, as such an analysis should be based solely on the intrinsic record—which here makes no mention of Hooke’s law.

Per Judge Moore, the majority further erred by essentially “disregard[ing]” step two of Alice by holding that claim 22 was “missing . . . any physical structure or steps for achieving the claimed result”. This was wrong in two respects, she argued. First, the majority neglected to address the conventionality of the claim invention’s physical features when searching for an inventive concept. Second, it misidentified the “claimed result”, which was not “a tuned liner; . . . [but rather,] the reduction of vibration in the propshaft”. After identifying a variety of physical features for which Judge Moore found there was at least a dispute of fact as to their inventiveness, she exclaimed, “[i]t is remarkable that the majority thinks that claims with all of these very physical, very concrete, very structural limitations are ‘missing any physical structure or steps’”.

Additionally, Judge Moore again criticized the majority for importing a version of enablement into the 101 analysis, characterizing it here as creating a “blended 101/112” defense—or “a new superpower[,] enablement on steroids”. While the majority characterizes the requirement that the claims identify how to achieve a result as a question of eligibility, Judge Moore insisted that its “true concern” was whether a skilled artisan would “know how to achieve that result without undue experimentation” (emphasis in original). “[T]his is a question of enablement, not eligibility”, reiterated Judge Moore.

Judge Moore also acknowledged some notable criticisms of the majority opinion by various stakeholders, stating that the decision has “sent shock waves through the patent community”—citing public statements from members of Congress, news articles, and academic pieces, and the amicus brief cofiled in this case by former Federal Circuit Judge Paul Michel, former USPTO Director David Kappos, and current US Senator Thom Tillis (R-NC). Those stakeholders have variously characterized the American Axle rulings as “unthinkable”, an “absurd result”, and as running counter to precedent that has treated the “specific, practical application[s] of the laws of thermodynamics in an industrial process” as patentable since the Nineteenth Century, among other criticisms cited in the dissent.

Judge Dyk’s En Banc Concurrence

Further sparring came in the five opinions that accompanied the Federal Circuit’s denial of en banc review. Among them was a concurrence by Judge Dyk (the majority opinion’s author), joined by Circuit Judges Evan J. Wallach and Richard G. Taranto. Judge Dyk defended the majority’s holding as “consistent with precedent and narrow in its scope” and circled back to his holding that claim 22 was ineligible for its failure to identify a specific means for achieving the desired result. He compared that claim to the one directed to the use of electromagnetism that was invalidated in O’Reilly v. Morse, arguing that “allowing the patentability of such broad claims impairs rather than promotes innovation and denies patent protection to real inventors”. In a footnote, Judge Dyk suggested that the same principle applies to eligibility challenges based on abstract ideas.

Judge Dyk also pushed back against criticisms from Circuit Judges Pauline Newman and Kara F. Stoll that the majority opinion would have precluded basic inventions like the “the telegraph, telephone, light bulb, and airplane”, stating that those fall outside the category of results-only claims invalidated in cases like O’Reilly.

Judge Chen’s En Banc Concurrence

Circuit Judge Raymond T. Chen also concurred, joined by Circuit Judge Evan J. Wallach, arguing as did Judge Dyk that the majority decision was consistent with precedent. Also like Judge Dyk, Judge Chen compared claim 22 to the patent invalidated in O’Reilly—going a step further by asserting that claim 22, “as drafted and construed, is substantively the same as Mr. Morse’s claim 8”, which explicitly claimed the use of electromagnetism to send messages—a claim that Judge Chen described as “disavow[ing] any implementation details from his specification”.

In addition, Judge Chen echoed the majority’s position that its holding did not stray into the realm of enablement, explaining that the eligibility requirement imposes a “threshold constraint on the claims, whereas enablement applies a second, different requirement to the specification’s support of those claims”.

Judge Newman’s En Banc Dissent

Circuit Judge Pauline Newman dissented from the decision to deny en banc review, joined by Judges Moore and Stoll as well as Circuit Judges Kathleen M. O’Malley and Jimmie V. Reyna. Similar to Judge Moore’s dissent, Judge Newman sounded an alarm over the broader harms posed by the Federal Circuit’s Section 101 jurisprudence, arguing that the court’s “rulings on patent eligibility have become so diverse and unpredictable as to have a serious effect on the innovation incentive in all fields of technology”.

Additionally, Judge Newman, too, characterized the decision as creating a threshold test denying patentability when claims invoke scientific principles—pointing out that “[a]ll technology is based on scientific principles—whether or not the principles are understood”. That threshold test, Judge Newman continued, runs counter to the limits set by the Alice decision, which aims to avoid construing judicial exceptions in a manner that “swallow all of patent law” by reiterating that claims applying abstract ideas “to a new and useful end” remain patent-eligible. Rather than the cases cited by the majority, Judge Newman argues that the Federal Circuit got it right in cases like Enfish v. Microsoft and In re: TLI Communications, which she characterized as emphasizing the importance of not over-simplifying the claims at issue.

Judge Stoll’s En Banc Dissent

Judge Stoll dissented as well, expressing concerns that the majority decision, despite efforts to cabin its holding, “introduce[s] additional questions—including how to apply the ‘nothing more’ test—that would benefit from further development and contemplation through en banc review”.

Judge Stoll took particular issue with the position of the majority and concurrences that the case is grounded in the precedent set in O’Reilly, countering that the claim held ineligible in that case was “distinguishable on its face . . . It was not limited to any particular machinery and was instead broadly directed to the use of electromagnetism, ‘however developed,’ for transmitting information”. Rather, she argued that claim 22 of the ‘911 patent was more akin to other Morse claims held eligible in O’Reilly.

Relatedly, Judge Stoll disagreed with Judge Chen that the O’Reilly lays out a distinct approach to eligibility, acknowledging the case’s importance as eligibility precedent but countering that there is no separate “O’Reilly test” as argued in his concurrence. Judge Stoll also questioned why, if this case presented such a straightforward application of such a test, it was not even mentioned in the district court opinion.

Judge Stoll further argued that other uncertainties also counseled further review, flagging the unclear bounds of the “nothing more test”, the propriety of applying that test without further factfinding, and the majority’s blurring of the line between eligibility and enablement.

Judge O’Malley’s En Banc Dissent

Finally, Judge O’Malley dissented, joined by Judges Newman, Moore, and Stoll, taking issue with how the majority decided the questions of law at issue based on grounds not addressed before the district court, and without giving the parties the chance to brief it. By doing so in this case, applying the new test itself rather than remanding to the district court, and issuing sua sponte constructions of previously undisputed terms to “distinguish claims and render them patent ineligible, or effectively so”, Judge O’Malley argued that the majority was engaged in “obstacle-avoiding maneuvers [that] fly in the face of our role as an appellate court”.

The Solicitor General’s Brief: The Federal Circuit Got it Wrong

The Solicitor General’s (SG’s) brief on behalf of the government aligned with several positions taken in the various dissents, arguing that the American Axle majority was wrong to hold that claim 22 was ineligible—and that the decision has broader implications for the state of eligibility caselaw:

Historically, such industrial techniques have long been viewed as paradigmatic examples of the ‘arts’ or ‘processes’ that may receive patent protection if other statutory criteria are satisfied. The court of appeals erred in reading this Court’s precedents to dictate a contrary conclusion. The decision below reflects substantial uncertainty about the proper application of Section 101, and this case is a suitable vehicle for providing greater clarity [emphasis added].

In particular, the SG emphasized that claim 22 takes a series of “concrete steps” to reach the desired outcome of “reduc[ing] multiple types of driveshaft vibration simultaneously” (the same result identified by Judge Moore, whereas the majority’s identified result was a “tuned liner”). Citing the Supreme Court’s decision in Diamond v. Diehr (upholding as eligible claims directed to an industrial process for rubber curing), the SG argued that “[i]ndustrial processes such as this are the types which have historically been eligible to receive the protection of our patent laws”.

The analogous claims from Diehr, continued the SG, are “illustrative” of the fundamental distinction laid out in Alice “between patents that claim the ‘building blocks’ of human ingenuity and those that integrate the building blocks into something more, thereby ‘transforming’ them into a patent-eligible invention”. In Diehr, the Court found that while several steps of the claimed process required the use of a mathematical equation (the Arrhenius equation), the claims were instead “‘drawn to an industrial process’ that used the Arrhenius equation ‘in conjunction with all of the other steps in the[] claimed process’”.

The SG further flagged a set of other relevant principles also laid out by the Supreme Court, including the “repeatedly recognized” notion, recounted in Alice, that “all inventions . . . embody, use, reflect, rest upon, or apply laws of nature, natural phenomena, or abstract ideas”, and the warning from Alice that the judicial exceptions should not be allowed to “swallow all of patent law” (as also invoked by Judge Newman). Also important was the principle that “the Section 101 inquiry is guided by historical practice and judicial precedent”, under which courts “should be skeptical of any assertion that a claim for the sort of process that has long been held patent-eligible, such as an industrial manufacturing process, is unpatentable under the ‘law of nature” exception”. Further relevant were the Court’s warnings that the exclusionary principle underpinning judicial eligibility exceptions, and Section 101 jurisprudence more broadly, is preemption—and that a “claim that confers exclusivity only over a narrow range of activity is less likely to implicate that concern” (citing Diehr).

Under those principles, the SG argued that the majority erred in its ruling of ineligibility for claim 22. Unlike in Mayo and Alice, the government contended, the claim does not “simply describe[]” or “recite[]” any natural law”; rather, it “recites a physical process for producing a particular type of automobile component”. That specific process, like “[e]very mechanical invention”, “requires use and application of the laws of physics”. While acknowledging that the claimed “tuning” step does require the use of Hooke’s law, the SG argued that “because all useful inventions that operate in the physical world depend for their efficacy on natural laws (whether known or unknown), such dependence by itself cannot render claim 22 patent-ineligible”. Rather, claim 22 was directed to an industrial process that is patent-eligible for the same reasons as the one in Diehr.

Moreover, the SG rejected the majority’s reliance on O’Reilly as “inapt”. Although it agreed with the majority’s holding that “claims that state a goal without a solution are patent-ineligible”, it also pointed out that under Diehr, “[t]he long-settled patent-law meaning of ‘process’ requires not merely a ‘result,’ but also ‘a mode of treatment’ or ‘series of acts’ that will ‘produce” it. Under that standard, and in contrast to the majority’s ruling, the SG asserted that “claim 22 goes well beyond identifying the ‘goal’ of reducing multiple modes of vibration”—and that the claim “does considerably more than ‘add the instruction ‘apply the law’’” (citing Mayo). Additionally, the SG explicitly cited Judge Moore’s dissent in arguing that the majority’s opinion conflated eligibility and enablement, agreeing that its “analysis blurs the two by demanding that the claims provide a degree of detail more appropriate to the enablement inquiry”.

That said, the government departed from Judge Moore as to issues of conventionality, implying that the judge did not go far enough by failing to “explicitly dispute the majority’s apparent premise that ‘conventional’ claim elements should be disregarded at step two of the Mayo/Alice framework”. While those cases do stand for the notion that a claim must include more than just “well-understood, routine, conventional activities” in the field at issue, other language from Mayo and Alice, and the surrounding context, “indicate that the Court did not intend to endorse a categorical rule that conventional claim elements should be disregarded in determining whether particular claims reflect an ‘inventive concept,’ or ‘add enough’ to natural laws or phenomena, so as to warrant patent protection”. Rather, the Court approvingly reiterated in Mayo—once again, citing Diehr—that the inventive concept inquiry must view the claimed process “as a whole”, as noted by the government. That requirement of “[h]olistic consideration of a claim at the second step is incompatible with an approach that ignores individual claim elements that are conventional in isolation”.

More broadly, the SG argued that certiorari is justified due to the “[o]ngoing uncertainty” that has beset the Federal Circuit and district courts. While acknowledging the “particular attention” that these problems have attracted in fields like medical diagnostics, the SG insisted that “the ‘inconsistency and unpredictability of adjudication’ extend to ‘all fields’”, citing the Federal Circuit’s decision on Yu v. Apple (on the patent eligibility of claims directed to a multi-lens camera) and Chamberlain v. Techtronic Industries (addressing the eligibility of a patent directed to a garage door opener). American Axle provides an ideal vehicle for addressing this uncertainty, the SG argued, due to the extensive factual record from the litigation below, because the case’s “splintered” opinions show how “the Federal Circuit is deeply divided over the proper application of this Court’s framework, and the content of that framework is central here”.

The SG concluded by recommending that the court grant certiorari for the first question presented in AAM’s brief, which concerns the bounds of Alice’s first step, and not the second, which asks whether both steps involve “questions of law for the court to decide or questions of fact for a jury to decide”. The SG contended that since the “answer to that satellite procedural question depends on the substantive Section 101 standard”, it would be “difficult” for the Court to address while uncertainty hangs over the substantive 101 inquiry. “If necessary, it may then address, in this case or a future one, whether applying that standard entails a legal, factual, or hybrid analysis”.

What Comes Next: Likelihood of Supreme Court Review

While it is impossible to predict the outcome with certainty, data show that the Supreme Court is more likely to grant certiorari for a patent case than for the overall body of petitions that it receives—especially when a CVSG is filed. [1] A 2020 study by Professor Paul R. Gugliuzza of the Boston University School of Law indicates that while the Supreme Court’s overall grant rate for paid certiorari petitions (i.e., those not filed in forma pauperis) was 4.3% from October Term (OT) 2002 through OT 2016, the grant rate in patent cases was 6.3%—a 32% increase [2] Moreover, in that same period, the “mere issuance of a CVSG” made a petition ten times more likely to succeed, pushing the grant rate up to 45.1%—with the Court agreeing with the SG’s recommendation to grant or deny 78.9% of the time. [3] That influence appears even higher for patent cases, for which the court agreed with the SG’s recommendation 93.3% of the time. [4]

Note also that the last administration’s Solicitor General, Noel Francisco, recommended the denial of certiorari in two other notable cases involving patent eligibility, albeit for reasons that do not appear to contradict the broader rationale underpinning the brief just filed by Prelogar. In Berkheimer, Francisco argued that the case was not a good vehicle for revisiting Section 101, because it primarily concerns procedural aspects of Section 101 (whether factual disputes render dismissal premature), and that the Court should instead grant review of a case for which substantive eligibility standards are central. Additionally, Francisco argued against granting certiorari in Hikma Pharmaceuticals v. Vanda Pharmaceuticals, a decision involving method-of-treatment claims involving natural laws, because the lower court allegedly reached the correct result in upholding the challenged claims; as such, he contended that the Court should hold out for a case in which addressing the underlying confusion over Section 101 caselaw would make a “practical difference”.

See “Supreme Court’s Denial of Berkheimer Appeal Leaves Alice Constraints in Place” (January 2020) for further context regarding those two amicus briefs.

For more on other recent Federal Circuit decisions on the eligibility of patents claiming mechanical inventions—including two rulings, Yu and Chamberlain, that the Supreme Court later declined to revisit despite the controversy they attracted—see “Federal Circuit Spars over Bounds of Abstractness Inquiry in Affirming Ineligibility of Camera Patent” (June 2021).

Finally, for details on the positions on Section 101 expressed to the Senate by USPTO Director Kathi Vidal, an experienced patent litigator who argued Chamberlain before the Federal Circuit, see here.

[1] Paul R. Gugliuzza, The Supreme Court Bar at the Bar of Patents, 95 Notre Dame L. Rev. 1233 at 1248 (2020) (likelihood of grant for patent cases); id. at 1253 (likelihood with CVSG), available at https://scholarship.law.nd.edu/ndlr/vol95/iss3/6/.

[2] Gugliuzza’s study treats petitions that are granted/vacated/remanded (GVR’d), an outcome that usually indicates little on the merits (id. at 1243), as being denied plenary review to enable a direct comparison with the Court’s official data on its overall grant rate. Without that exclusion, the grant rate is slightly higher for patent cases, at 6.6% (id. at 1247). The study also includes only paid petitions, as those filed in forma pauperis are rarely granted, and “certainly not in any patent case since 1982” (id. at 1241)

[3] Id. at 1256.

[4] Id. at 1255.