Delaware Chief Judge Connolly Pulls Back the Curtain on West Texas Plaintiff with Familiar Ties

Delaware Chief Judge Colm F. Connolly has been at the center of a debate over litigation transparency since he imposed stringent new disclosure requirements in his courtroom last April. However, while patent plaintiffs with suits before Judge Connolly have been dealing with resulting compliance issues for several months, the impact is now being felt outside his district as the result of a multijurisdictional discovery dispute involving the once-prolific litigant WSOU Investments, LLC (d/b/a Brazos Licensing and Development) (“WSOU”). In January, Salesforce—a defendant in ten WSOU cases brought in the Western District of Texas—filed a Delaware motion asking the court to force two Delaware entities with allegedly “substantial interests” in WSOU to provide information on their ownership and control. WSOU filed a motion to seal much of that material, sought by Salesforce in support of a license defense. Last week, Judge Connolly not only denied that sealing motion but also rolled back all prior redactions in the case—revealing new details on the asserted license, which stems from WSOU’s alleged ties to an individual behind another well-known NPE.

WSOU filed the underlying litigation against Salesforce in December 2020, each complaint asserting a single patent from a large portfolio acquired from Nokia (including Alcatel-Lucent). While WSOU’s disclosures in those cases painted a limited picture of its corporate structure, revealing that its parent is WSOU Holdings, LLC, other public records have revealed further details about who is behind the plaintiff—in particular, the ties now at issue: Craig Etchegoyen, the cofounder and CEO of Australian NPE Uniloc Corporation Pty. Limited, has signed patent assignment agreements filed with the USPTO (e.g., this one) on WSOU’s behalf (as a member).

It is WSOU’s connection to Uniloc, via Etchegoyen, that formed the basis of Salesforce’s aforementioned license defense, which the company apparently raised starting in mid-2022 when the case was still in discovery. Salesforce subsequently described (in its Delaware motion to compel, as filed in redacted form on January 20) its license defense as “case-dispositive” and as arising “from a settlement and license agreement that Salesforce signed with Uniloc, a different patent holding company founded by the same individual that founded WSOU Investments, Craig Etchegoyen”. In support of this defense, Salesforce explained that it was seeking information related to WSOU Holdings, LLC and WSOU Capital Partners, LLC, two Delaware LLCs that “each own substantial interests in WSOU Investments”, including documents and testimony related to their “formation, structure, governance, and ownership”, the relationship between the two, and their relationship with WSOU. Per Salesforce, it had sought this information directly from WSOU, but the plaintiff indicated to the court that it did not have “possession or custody” of it—while WSOU Holdings and WSOU Capital were unwilling to provide it in response to subpoenas against them, raising what Salesforce called “boilerplate objections”.

Salesforce also filed similar motions to compel in two other jurisdictions for an additional two entities in WSOU’s ownership chain. It brought one such action in Nevada with respect to Orange Holdings, an entity formed there and controlled by Etchegoyen, which allegedly “owns substantial interests in WSOU Capital and WSOU Holdings, and through those interests, owns the largest individual share of WSOU Investments”. Salesforce filed another motion to compel in the District of Columbia seeking the compliance of OCO Capital Partners LP, “the investment manager of a Cayman Islands limited partnership that is the second largest shareholder of WSOU Investments”. In each case, including the Delaware one, the parties filed motions to seal information apparently designated by WSOU as confidential. WSOU also moved to transfer each action back to the Western District of Texas.

While the Nevada court granted the parties’ motions to seal together on February 27, the outcome of the Delaware action—which, as noted above, was assigned to Judge Connolly—was quite different.

Although Judge Connolly had previously granted Salesforce’s motion to file its unredacted brief under seal, he adopted a more critical approach as a result of WSOU’s subsequent motion to file a variety of its own materials under seal: its reply brief; its brief in support of its motion to transfer; and its disclosures made in attempted compliance with the court’s two April 2022 standing orders, alluded to above, which require the wide-ranging disclosure of details regarding a party’s ownership/control and certain third-party litigation funding. WSOU’s motion, per Judge Connolly, “prompted [him] to review all the filings the parties have maintained under seal to date”.

Judge Connolly dispensed briefly with most of the sealing requests—some of which he decided in consultation with the presiding West Texas magistrate judge, Derek T. Gilliland. Beginning with the parties’ briefs, he found that there was no good cause for maintaining those filings under seal, stating that he had shared the briefs with Judge Gilliland, who reviewed them and agreed. Turning next to the parties’ exhibits, Judge Connolly kept the transcript of Judge Gilliland’s discovery hearing sealed because the latter judge had not yet unsealed them in his own court. However, Judge Connolly held that another swatch of remaining exhibits should be unsealed—including copies of the subpoenas, motions to compel, a scheduling order, docket sheets, and certain communications between parties’ counsel that WSOU had sought to seal; and certain public documents related to the formation and management of Orange Holdings listed in Salesforce’s motion to seal.

Judge Connolly focused in particular on the remaining Salesforce exhibits, its Uniloc settlement agreement and the operating agreements with WSOU, WSOU Capital, and WSOU Holdings, noting that “[t]hese documents lie at the heart of the parties’ dispute before me”. While he found that no good cause existed to seal the documents in their entirety, he found that “good cause exists to seal bank account and taxpayer identification information contained in the documents”, and that “good cause may exist to maintain under seal certain dollar amounts (but not ownership percentages)”. Judge Connolly gave the parties ten days (i.e., until March 10, 2023) to propose redactions to those documents.

Judge Connolly was more explicitly critical in his finding that there was no good cause to seal WSOU’s Delaware disclosure statement, which he noted “merely identifies—but only partially—the real parties behind WSOU”. WSOU Capital and WSOU Holdings had argued in their motion to file under seal that the “identities of certain of the entities listed on the Corporate Disclosure Statement are highly confidential”, further characterizing this information as “sensitive non-public information”.

Judge Connolly pushed back on that characterization, countering that “[t]he district court is not a star chamber”, meaning one that is secretive, arbitrary, and oppressive (a reference to the Star Chamber Courts, an English tribunal widely perceived as such before its abolishment in 1641). Rather, he explained, “[w]e are a public institution in a democratic republic and the public has a right of access to our filings and proceedings. That right is founded in the common law and ‘antedates the Constitution’” (citation omitted). Although acknowledging that the “public’s right of access is not absolute”, he underscored that “it is strongly presumed”. That presumption “can be overcome only if a party demonstrates that public disclosure of a filing will result in ‘a clearly defined and serious injury’”, and Judge Connolly determined that was not the case here: “Public disclosure that an individual has an ownership interest in an entity created by a state cannot be said to constitute an injury. Corporations and LLCs may offer individuals protection from liability, but they don’t entitle individuals to anonymity in court proceedings. ‘The people have a right to know who is using their courts’” (citations omitted).

Much of the information covered by the unsealing order remains inaccessible to the public for now. However, the parties’ briefs have been unsealed, revealing additional contours of the dispute and the nature of the evidence sought. In particular, Salesforce’s motion to compel brief explains the terms from the Uniloc agreement (the full version of which remains sealed) that Salesforce has cited for its license defense: The agreement grants the company a license to all patents that “Uniloc at any time (past, present, or future) had or has the ability or right to enforce or license”. Crucially, per Salesforce’s summary, the term Uniloc is defined to include both Craig Etchegoyen as well as any “Affiliates”: “‘Uniloc’ means Uniloc Luxembourg S.A. and Uniloc USA, Inc., their predecessors, successors, and Affiliates . . . (including, but not limited to, Craig Etchegoyen)” (emphasis in brief). Taken together, Salesforce asserts that this language gives it a license to any patents that “[Craig Etchegoyen] at any time (past, present, or future) had or has the ability or right to enforce or license”.

Indeed, the company quotes Judge Gilliland as having stated during a December discovery hearing that this language was “extremely broad” in its definition of “Uniloc”, and that “at least for discovery purposes, it gets [Salesforce] to the point where they’re entitled to explore whether [Mr. Etchegoyen]” controls WSOU Investments or the asserted patents as part of its license defense”. This led the court to grant Salesforce’s motion to compel WSOU itself to provide such information (though, as noted above, WSOU stated in response that it did not possess or have custody of that information), and to advise Salesforce that any motion to compel the other entities (WSOU Capital, WSOU Holdings, and Orange Holdings) should be filed “wherever that needs to be appropriately filed”.

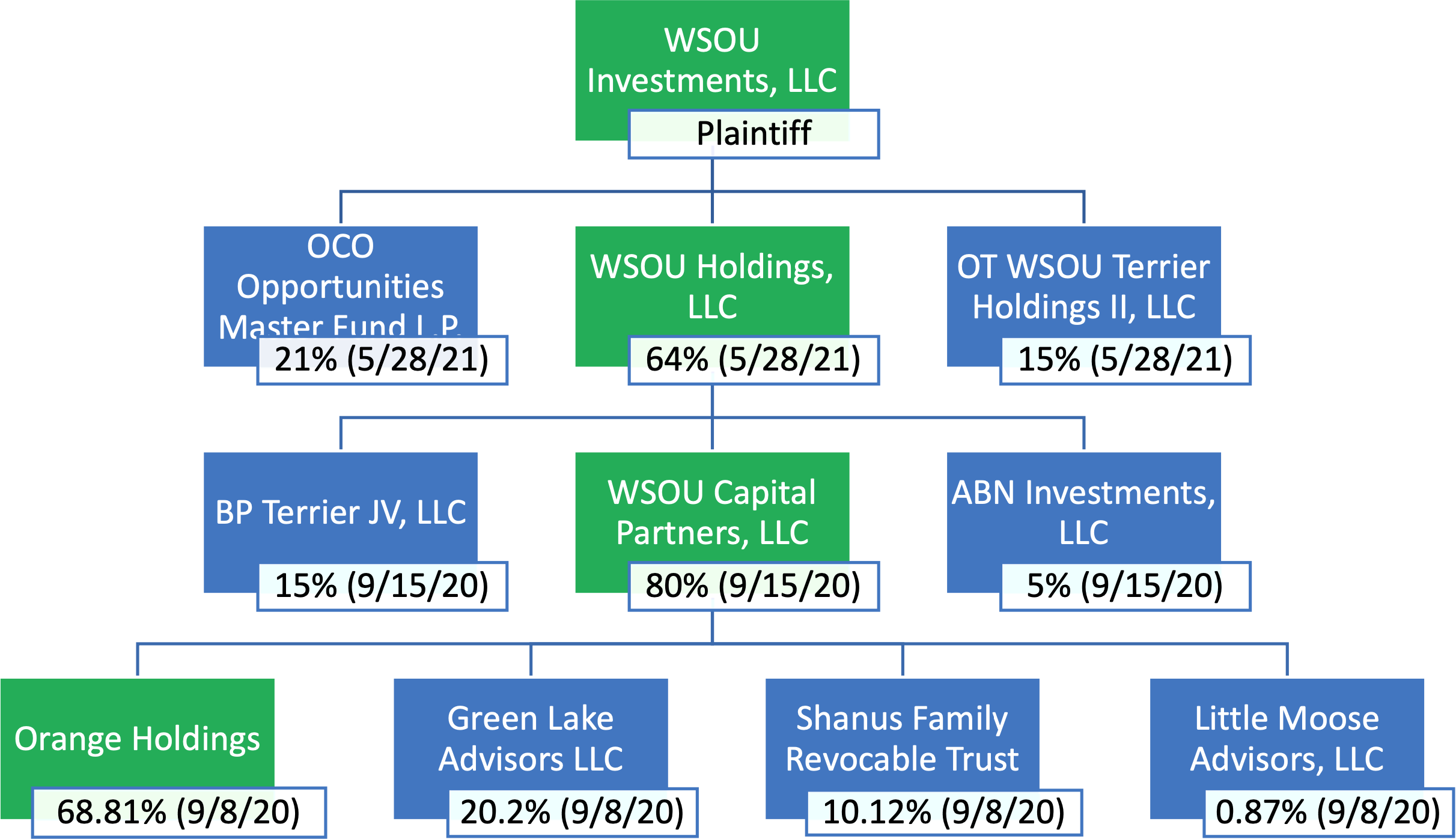

Other unsealed portions of the brief include Salesforce’s summary of the evidence it has collected on this issue to date. The company alleges that this evidence “strongly indicates that (1) Orange has always been under the control of Mr. Etchegoyen, and (2) Orange has had control of WSOU Investments from its inception in 2017 to the present via WSOU Holdings and WSOU Capital”. In detailing this ownership history, Salesforce included a chart that “summarizes the current ownership interests in (i) WSOU Investments by WSOU Holdings (64%), (ii) WSOU Holdings by WSOU Capital (80%), and (iii) WSOU Capital by Orange (68.81%) based on documents produced thus far in the WSOU Patent Litigation”:

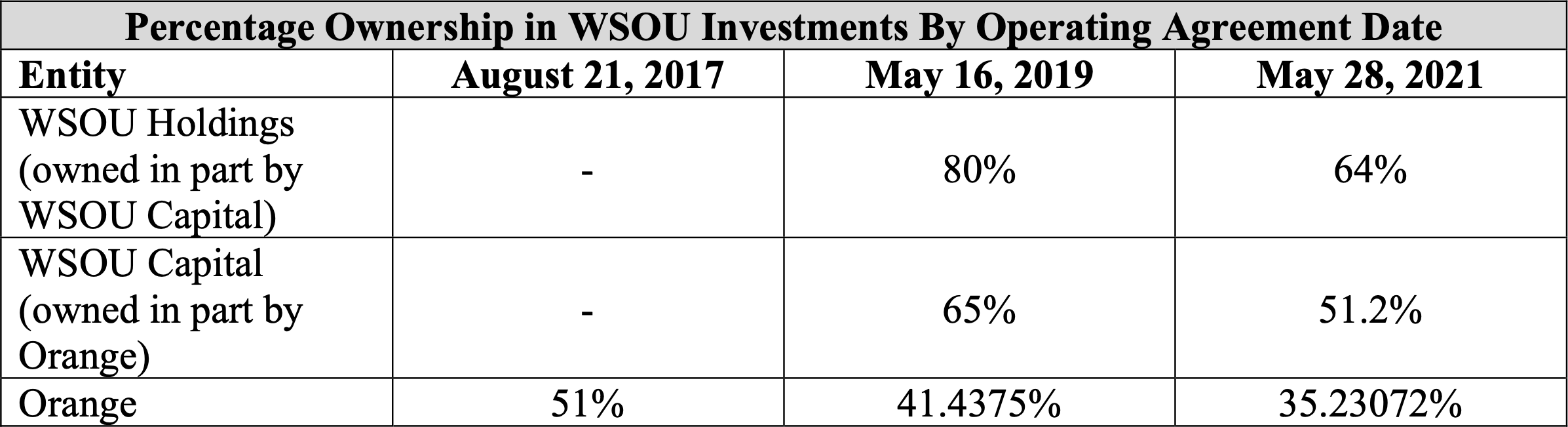

The unredacted brief also broke down the ownership percentages held by WSOU Holdings, WSOU Capital, and Orange Holdings as of the “effective dates of WSOU Investments’ three operating agreements”:

On March 1, the court granted a request from WSOU Capital and WSOU Holdings to keep a previously filed exhibit sealed “in order to prevent information about minor children from being publicly disclosed”, with a redacted version to instead appear on the public docket. The information in question is likely the names of Etchegoyen’s children, given his testimony that “the majority owners of Orange’s investment in WSOU Investments are technically trusts named after his children”. As of this article’s publication date, the parties have not otherwise proposed any further redactions in response to the unsealing order, which must occur by March 10 as noted above.

This dispute is not the first in which a WSOU defendant has cited Etchegoyen’s connections to Uniloc. For instance, ZTE has filed a motion to dismiss 11 of WSOU’s cases against it for lack of subject matter jurisdiction, alleging that the plaintiff “never actually acquired the full exclusionary rights of the patents asserted here”. In making that argument, the defendant drew parallels to an earlier ruling that the improper distribution of patent rights in certain Uniloc cases, including some rights that a court found had reverted back to a Fortress Investment Group LLC subsidiary, required their dismissal for lack of standing:

This is not the first time Mr. Etchegoyen failed to acquire sufficient rights to patents before asserting them. In just the last two years (overlapping with the suit filings here), Uniloc—another NPE founded by Mr. Etchegoyen—has had lawsuits against Apple and Google dismissed because it did not have exclusionary rights in the asserted patents. Given the tarnished Uniloc name and failed patent ownership history, this NPE rebranded as WSOU . . .

This case is also not the first time that a patent defendant has argued that a plaintiff’s corporate relationships establish a license under a prior agreement. Intel, the sole defendant in the campaign being waged by another Fortress subsidiary, VLSI Technology LLC, has argued that it has a license to the VLSI portfolio as a result of Fortress’s 2020 acquisition of NPE Finjan Holdings, Inc. The defendant argues that its existing license with Finjan, which covers Finjan “affiliates”, now encompasses VLSI, as VLSI allegedly became such an affiliate when Fortress purchased Finjan.

While Judge Albright denied Intel’s motion to amend its answer to assert that defense in April 2022 in one of VLSI’s West Texas cases, Judge Connolly allowed Intel to do so in the Delaware leg of the campaign that same July. However, in December, the parties settled the Delaware part of their litigation, with Intel reportedly paying “nothing to VLSI” and the plaintiff agreeing to a covenant not to sue Intel, or its suppliers or customers, over the patents-in-suit. See here for more background on that dispute.

More on the WSOU campaign can also be found here—including a notable setback that saw its first trial fizzle late last month.