NXP Puts Pen to Paper

Late last year, after a storm of Bell Semiconductor, LLC (Bell Semic) complaints filed in various district courts targeting defendants over the provision of semiconductor devices manufactured using certain design tools, Cadence and Synopsys together filed a declaratory judgment (DJ) action in the District of Delaware, as Siemens separately did. Many of the other cases, if not dismissed, were stayed pending the DJ outcomes—many but not all. Southern District of California Judge Marilyn L. Huff let four consolidated cases that Bell Semic had filed against NXP Semiconductors proceed. Bell Semic had defeated early Alice challenges based on the purported need for claim construction, the cases moved forward, and on June 13, Judge Huff issued her Markman ruling. NXP has now filed “supplemental briefing” in support of its prior eligibility challenges, the defendant attempting to show to the court that putative abstract ideas like “prioritizing dummy regions in a circuit design such that dummy regions closest to clock nets are addressed last” are “nothing more than a mental process that can be performed using pencil and paper” by submitting a set of figures actually drawn by someone’s hand.

Bell Semic asserted two patents (6,436,807; 7,007,259) in its earliest Southern District of California complaint against NXP (3:22-cv-00594), filed in April 2022. Both patents are generally related to “dummy metal fill”, which adds additional, nonfunctional metal to a wafer surface to ensure even results from a semiconductor manufacturing process called Chemical Mechanical Planarization/Polishing (CMP). Claim 1 of the ‘259 patent reads:

1. A method for inserting dummy metal into a circuit design, the circuit design including a plurality of objects and clock nets, the method comprising:

(a) identifying free spaces on each layer of the circuit design suitable for dummy metal insertion as dummy regions; and

(b) prioritizing the dummy regions such that the dummy regions located adjacent to clock nets are filled with dummy metal last, thereby minimizing any timing impact on the clock nets.

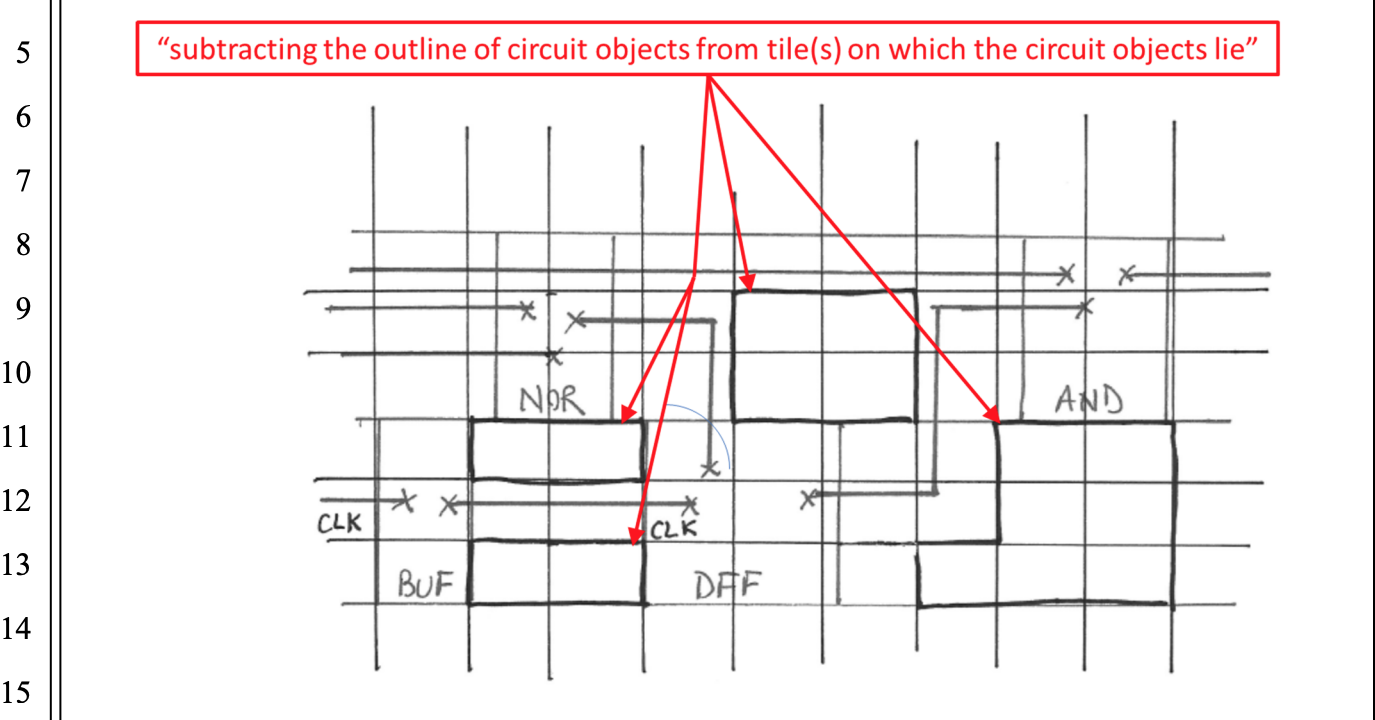

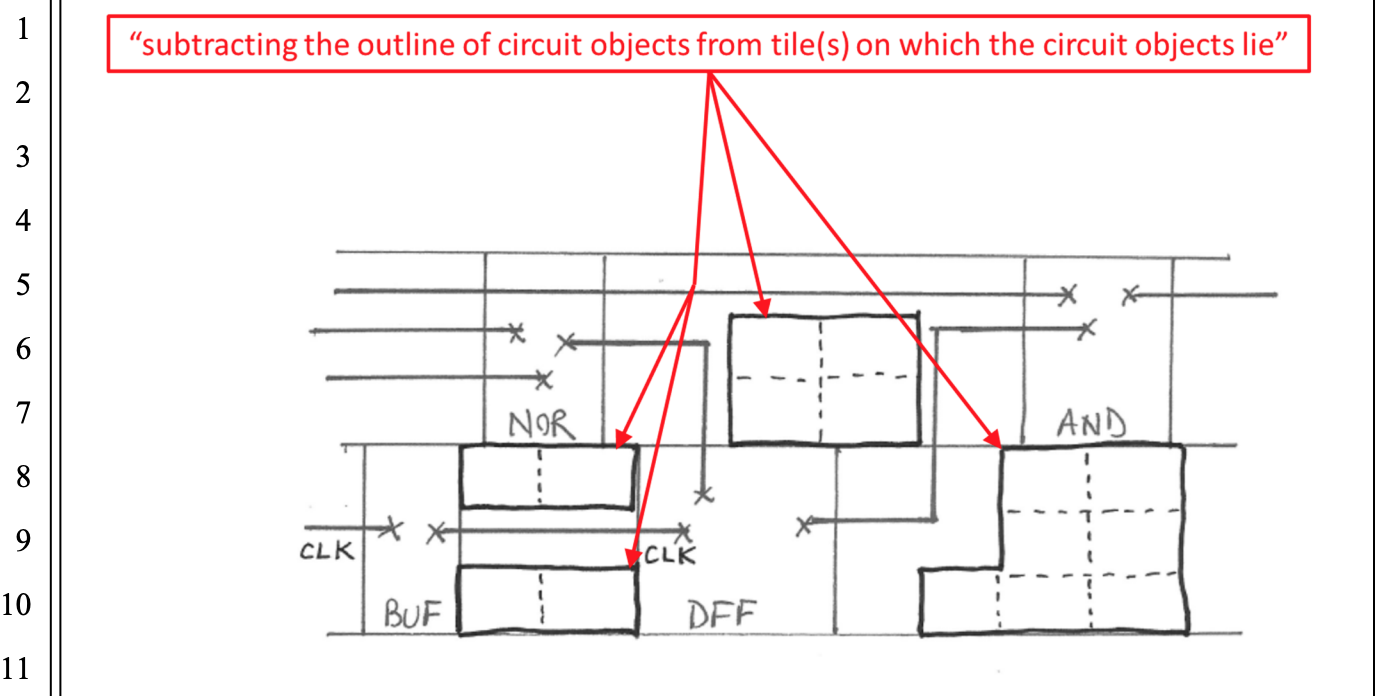

NXP previously attacked this claim as patent-ineligibly drawn to the abstract idea of “prioritizing dummy regions in a circuit design such that dummy regions closest to clock nets are addressed last”. The court construed step (a) to mean “creating a list of dummy regions on each layer of the circuit design, obtained from subtracting the outline of circuit objects from tile(s) on which the circuit objects lie, without hard coding a large stay-away distance between dummy metal and clock nets” and the step (b) to mean “ordering the list of dummy regions such that dummy regions next to/adjoining clock nets are filled last, without hard coding a large stayaway distance between dummy metal and clock nets, where the fill is inserted in a single run”.

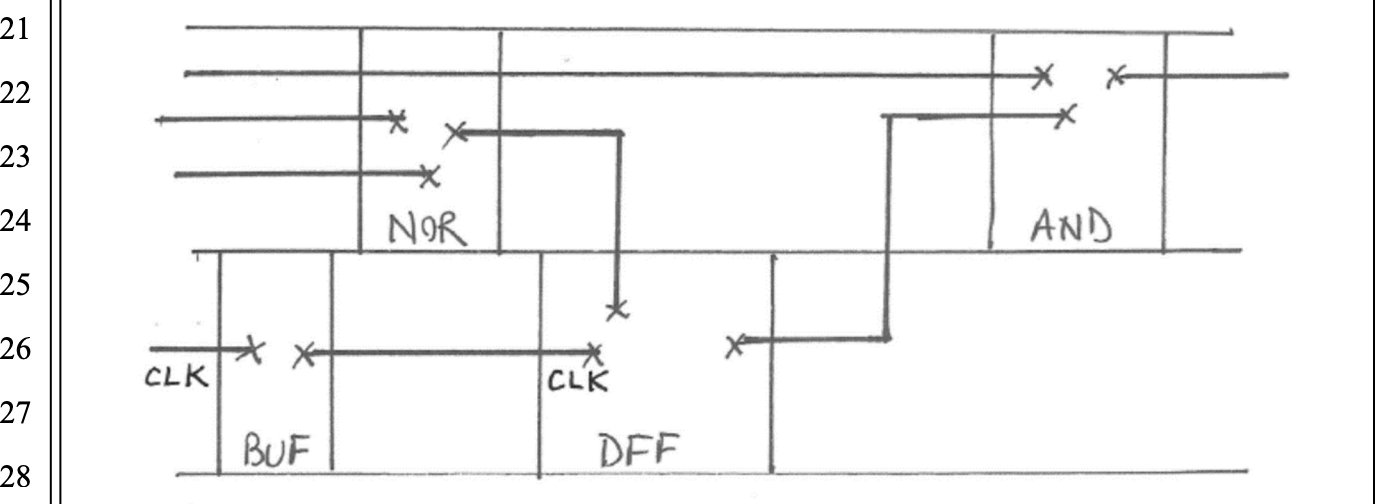

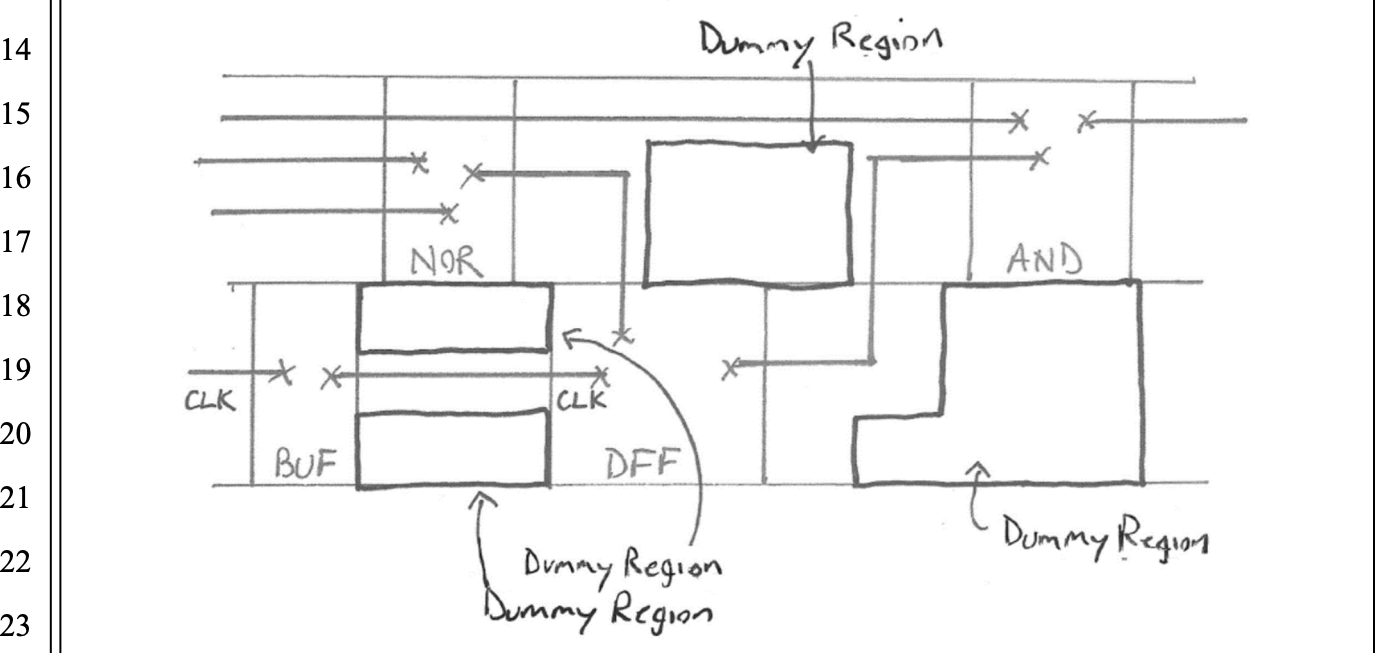

Per NXP, neither party argued that either term required a computer or computer software, the court’s constructions requiring “no computer components, computer software or techniques”. NXP also notes that the court separately construed the terms “adjacent” and “minimizing” (appearing in step (b)) but that “[n]either term affects the eligibility analysis, as neither term nor the Court’s constructions require the use of computers”. Given the language of claim 1, as construed by the court, NXP sets out in its supplemental briefing to show—through a series of hand-drawn figures—that this claim is directed to mental steps that can be performed using pencil paper. The first figure depicts an example circuit design to which to apply claim 1’s steps:

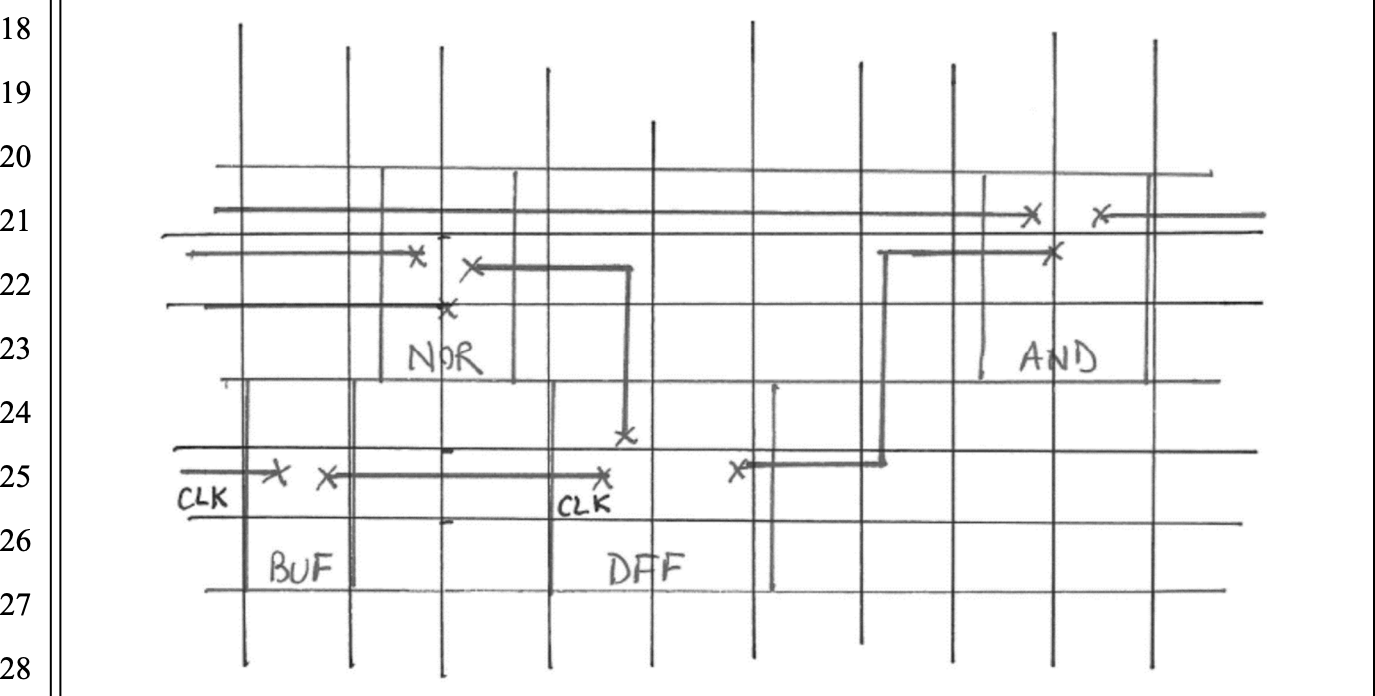

Per NXP, illustrated above are typical “connected circuit objects (a NOR gate (‘NOR’), an AND gate (‘AND’), a buffer (‘BUF’), and a D-type flip-flop (‘DFF’), as well as a clock net (‘CLK’)”. As a first step, which NXP contends is entirely conventional, the above circuit design is partitioned into rectangular regions known as tiles to arrive here:

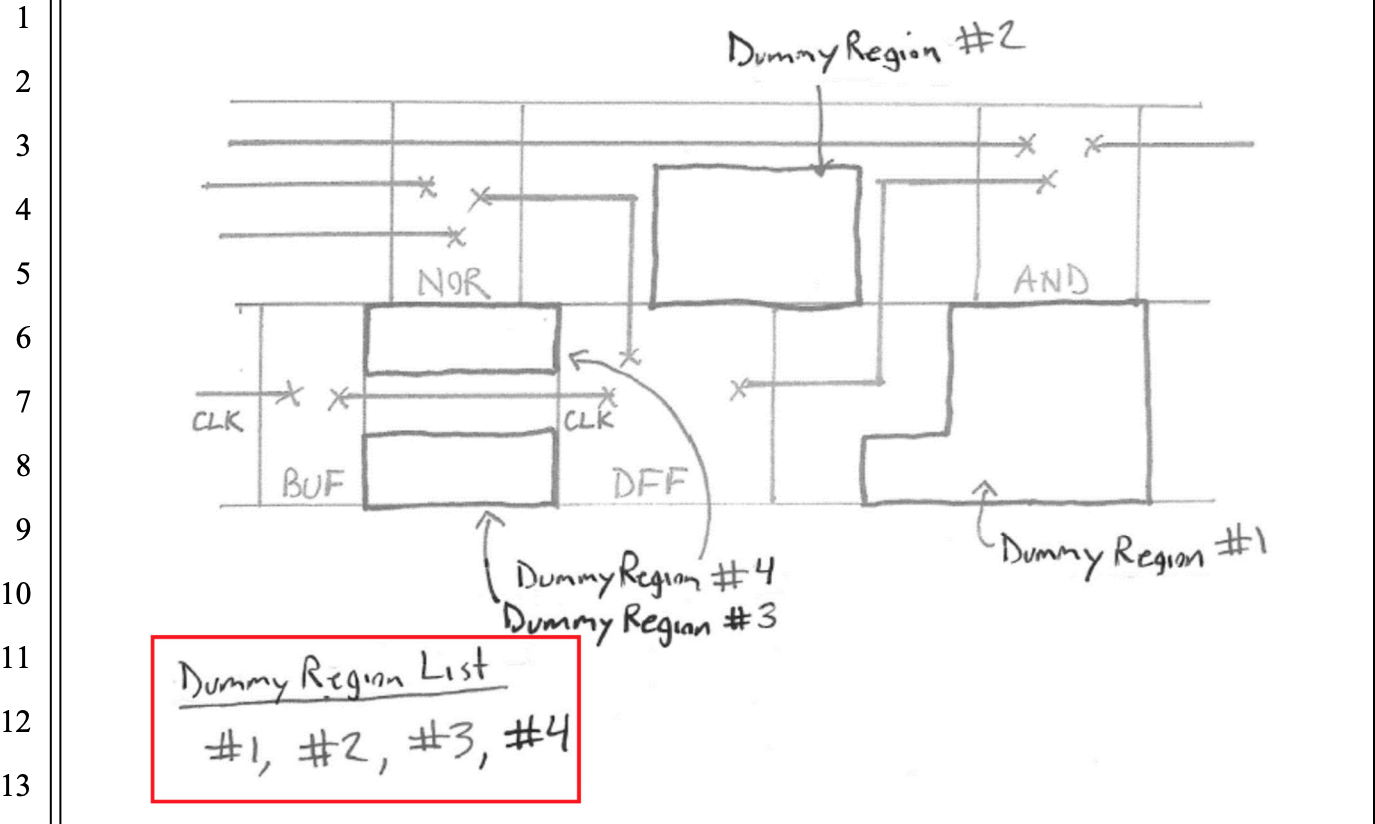

Next, NXP argues that a person of ordinary skill in this art could “then create [a] list of dummy regions by ‘subtracting the outline of circuit objects from tile(s) on which the circuit objects lie’”, by identifying “free spaces” outlined with thicker lines (presumably darkened with a pencil) and here further highlighted by red arrows pointing to them (presumably generated with a computer):

To conform with the court’s construction, NXP comments, “As can be seen, when drawn, there are no large hard-coded stay away distances”. To aid in viewing these identified free spaces (i.e., dummy regions), NXP provides the same figure with the “tile lines outside the dummy regions” erased:

This process “results in four free spaces, which are identified as dummy regions”:

Those dummy regions can then be listed, according to NXP, with just pen and paper:

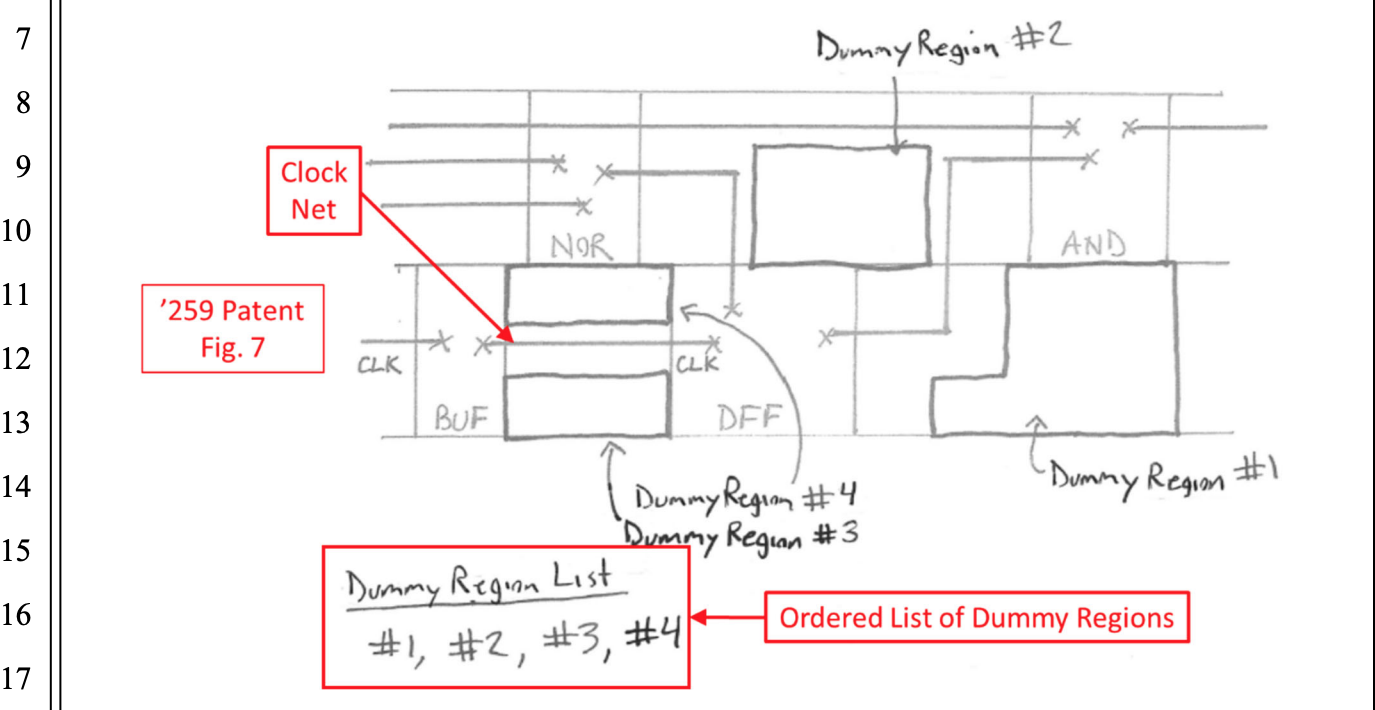

That completes the depiction of step (a) in claim 1. NXP then turns to step (b), which, again, requires (per the court’s construction) “ordering the list of dummy regions such that dummy regions next to/adjoining clock nets are filled last, without hard coding a large stayaway distance between dummy metal and clock nets, where the fill is inserted in a single run”. NXP first depicts ordering the dummy regions by distance from the clock net, farthest first:

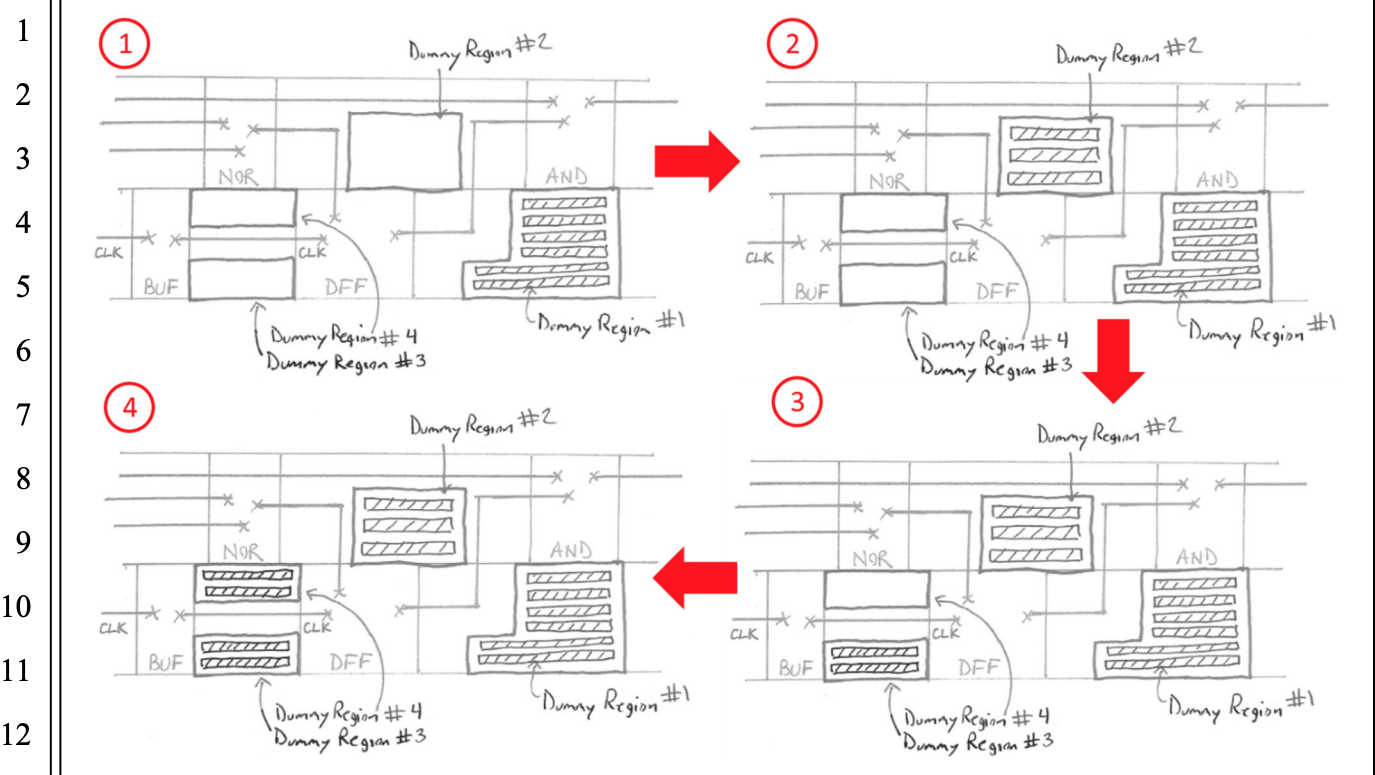

(The red box with “‘259 Patent Fig. 7” apparently refers to this figure, as the seventh figure related to the ‘259 patent in NXP’s brief, not to a Figure 7 within the ‘259 patent, as that patent has no Figure 7.) Next, NXP purports to show with pencil and paper—drawing “hatched rectangles” as metal going in—the dummy regions being filled in their “mentally-created” prioritized order:

NXP explains this process in words as well: “As seen, the dummy region furthest from the clock net, ‘dummy region #1,’ is filled first, followed by ‘dummy region #2.’ Then, ‘dummy region #3,’ the next closest dummy region to the clock net, is filled. And finally, ‘dummy region #4,’ the last dummy region in the ordered list, is ‘filled last.’ Plainly, the prioritizing was done in a ‘single run,’ as there was no re-visiting of the fill done in an earlier iteration of the drawing process, and there is no large hard-coded stay away distance around the clock net”.

The defendant then argues that none of the court’s other constructions impact this illustrated analysis and in fact further demonstrate that claim 1 of the ‘259 patent is not only directed to an abstract idea (here, a mental process) but also has no additional inventive concept in its language to save it. NXP both repeats that nothing about those constructions requires a computer and draws heavily on the Federal Circuit’s October 2016 opinion in Synopsys v. Mentor Graphics, affirming the Northern District of California’s invalidation of patent claims from the same field. (Mentor Graphics was acquired by Siemens in 2017.)

There, the court characterized the claim under consideration as directed to the abstract idea of “translating a functional description of a logic circuit into a hardware component description of the logic circuit”, a “mental process” that does not require the use of a computer. The only putative additional inventive concept that the court identified there (the use of “assignment conditions”) is characterized as “merely aid[ing] in mental translation as opposed to computer efficacy”. The claims under consideration were thus invalidated.

NXP runs through such a pencil-and-paper illustrative analysis, as used for claim 1 of the ‘259 patent, with respect to the other patent asserted in the April 2022 complaint, the ‘807 patent, as well as one (7,149,989, generally related to verifying an integrated circuit design to ensure adherence to process rules and overall manufacturability of the integrated circuit design for a specific technology) of the two patents (7,260,803, another “dummy metal” patent) asserted in an August 2022 complaint (3:22-cv-01267) and the only patent (7,396,760, also a “dummy metal” patent) asserted in Bell Semic’s November 2022 complaint against NXP (3:22-cv-01794).

Litigation as to the ‘803 patent in the -1267 case and as to a sixth patent (7,231,626, broadly related “to methods for implementing an [engineering change order] in a semiconductor chip design through selective editing of the design”) in Bell Semic’s October 2022 complaint in the Southern District of California (3:22-cv-01527) was stayed pending the resolution of actions that Bell Semic filed before the International Trade Commission (ITC). However, Bell Semic withdrew its ITC complaints, prompting Judge Huff to lift the district court stays as to these two patents, doing so on June 22.

As noted, Judge Huff consolidated the -594, -1267, -1527, and -1794 cases for pretrial purposes before her, with the -594 suit in lead. However, these Southern District of California cases are not the only suits that Bell Semic has filed against NXP. In its other campaign (as a formal matter), which does not have at its core allegations concerning the use of others’ design tools, Bell Semic has twice sued NXP, in a March 2020 complaint filed in the Western District of Texas and asserting ten semiconductor fabrication patents (1:20-cv-00611) and in another November 2022 complaint, this one filed in the Central District of California asserting three packaging patents (8:22-cv-02133).

The -611 case has been stayed pending the completion of certain inter partes reviews of the patents-in-suit. Bell Semic moved to lift the stay, but that motion was denied in January of this year by District Judge Lee Yeakel before he retired from the bench. In early May 2023, Judge Yeakel was removed from the case, but a new judge has yet to be assigned. The -2133 suit has also seen a judge reassignment. Originally on the docket of District Judge David O. Carter, it was just moved to District Judge Hernan D. Vera, who took the federal bench on June 15, 2023. The parties have submitted a status report that suggests, if the schedule holds, that they have just entered claim construction, exchanging disputed terms and proposed constructions last month.

Meanwhile, in the design tool DJ actions, Siemens settled with Bell Semic, ending that case before Judge Connolly in early May 2023. Bell Semic, Cadence, and Synopsys submitted a joint claim construction brief in their case on June 23, addressing disputed terms from the ‘803 and ‘626 patents—the ones as to which Judge Huff had imposed a stay. Judge Connolly earlier ordered that the parties will be bound by the claim construction ruling from Judge Huff as to the other patents. Farnan LLP has withdrawn from its representation of Bell Semic, for which Devlin Law Firm LLP continues as counsel. A claim construction hearing is set for July 20; the final pretrial conference, for December of this year.

Should either Cadence or Synopsys wish to take up NXP’s pen-and-paper Alice challenge to Bell Semic’s six asserted patents, it would have to do so by September 18, the deadline for parties to file dispositive motions.